Digital Identity Risk Assessment Playbook

| Version Number | Date | Change Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 06/15/2025 | Updated based changes to NIST SP800-63-4 |

| 1.2 | 12/29/22 | Fixed heading typo, updated Appendix A. links |

| 1.1 | 11/17/21 | Inserted Key Point box at the end of Step 2. |

| 1.0 | 09/13/20 | Initial Draft |

Acknowledgments

This playbook reflects the contributions of the Digital Identity Risk Assessment working group of the Identity, Credential, and Access Management Subcommittee (ICAMSC). The working group was co-chaired by members from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Contributions were made by the members of services or agencies representing the Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Department of Defense (DOD), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Justice (DOJ), Department of the Treasury (USDT), Department of Transportation (DOT), and General Services Administration (GSA).

Introduction

A digital identity represents each individual engaged in an online transaction. However, in some cases an individual could have multiple digital identities and the real-life identity may not be known when used to access a digital service.1 When confidence in an individual’s real-life identity is required to provide trust between the individual and the service being accessed, the identity proofing process establishes that the individual is who they claim to be and binds that identity to the authenticator used to access the service. The digital authentication process provides reasonable risk-based assurances that the authenticator being used is in the control of the individual who is authorized to access the service. This playbook presents guidance in applying the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines series to perform a Digital Identity Risk Assessment (DIRA).

Purpose

Most federal agencies offer services through an IT system or application, such as a website, to their employees, other agencies, and the public. To access an application, users may need to provide identity information, create an account, and log in. These actions are part of the digital identity and authentication process.

DIRAs determine the assurance levels for the digital transactions that involve digital identity or require human authentication.2 When agencies build or buy applications that use the most current identity proofing and authentication standards, they protect both the digital transactions, and the user and agency data behind the applications.

This Digital Identity Risk Assessment playbook helps federal agency Chief Information Officer (CIO) and Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) teams and business application owners to:

- Update and maintain consistent processes;

- Determine whether an agency application requires a DIRA;

- Integrate DIRA into agency Risk Management Framework (RMF) processes; and

- Learn practices to implement DIRA processes.

NIST publishes implementation guides3 and frequently asked questions (FAQs)4 for agencies and service providers to use to create information technology solutions to meet these standards. This playbook promotes consistency, effectiveness, and efficiency in your agency’s processes.

How to Use This Playbook

This playbook is divided into three major sections. Read the entire playbook or jump directly to the section that will help your agency.

- High-Level DIRA Process - A step-by-step guide on how to approach a DIRA process for each agency.

- Agency Process Plays - Six plays to create efficient and consistent processes. For example, Play #4 includes a shortcut decision tree for a streamlined DIRA for some applications.

- Appendices - Example diagrams and templates, and references to policies and standards to use in your agency for communications.

Scope

The DIRA playbook applies to all federal Information Technology (IT) systems and applications that need identity proofing and authentication.5 This playbook complements the following standards and policy:

- NIST Special Publication 800-63-4: Digital Identity Guidelines

- Office of Management and Budget Memorandum (OMB) M-19-17: Enabling Mission Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management

All agency information technology systems should use the DIRA process as part of the Risk Management Framework (RMF) and Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) processes. Business owners and information security officers produce a Digital Identity Assessment Statement (DIAS) to document the assurance levels determined by collecting and analyzing the system or application data as part of the assessment process.

This playbook does not apply to:

- Non-person entities,6 such as devices, Robotic Process Automation (RPA), or Machine Learning;

- Facilities access;

- Federation Assurance Level 3 solutions;7 or

- National security systems (NSS).8

The following sections describe a basic DIRA process and provide plays to help you implement efficiency into your agency’s processes.

High-Level DIRA Process

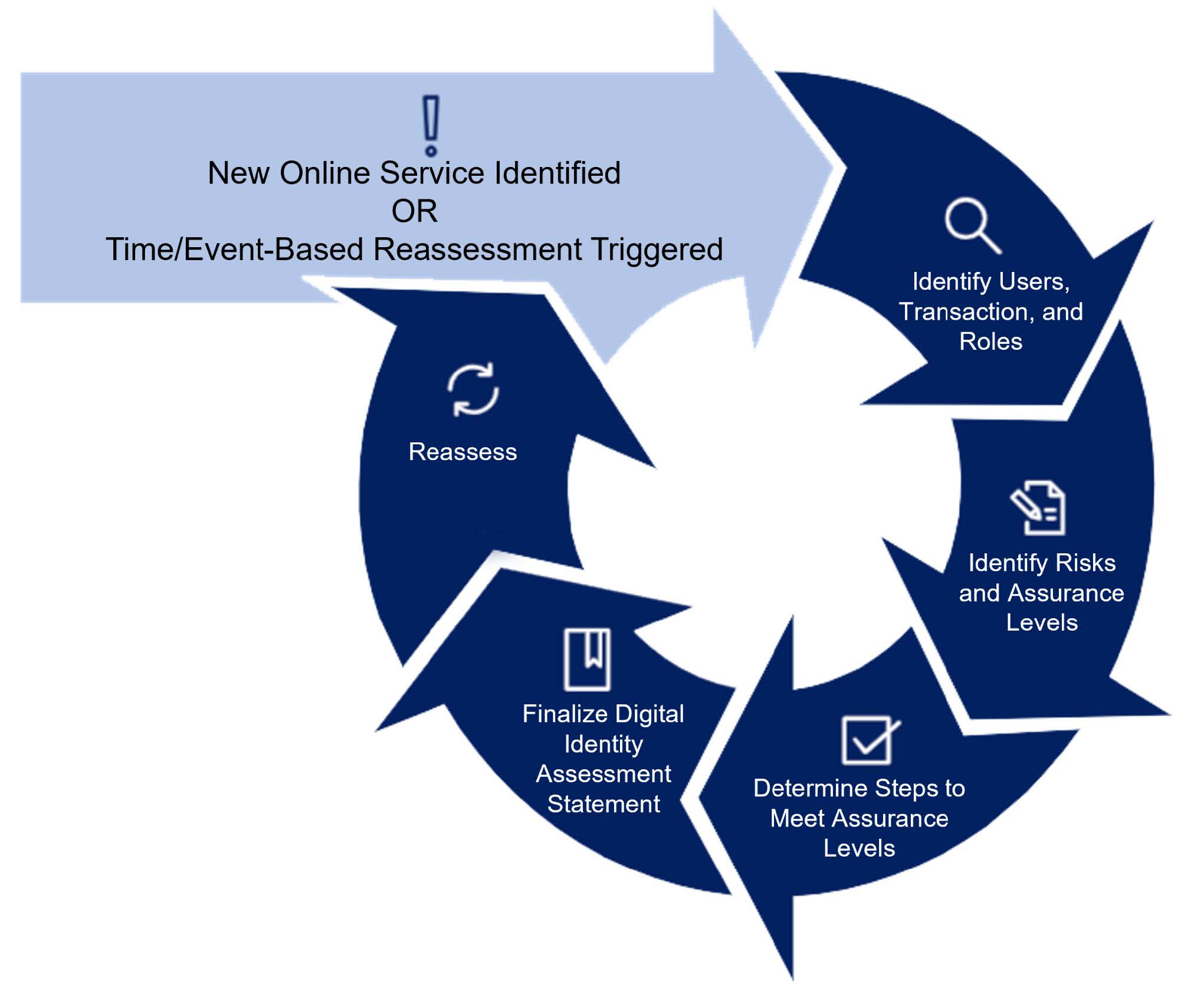

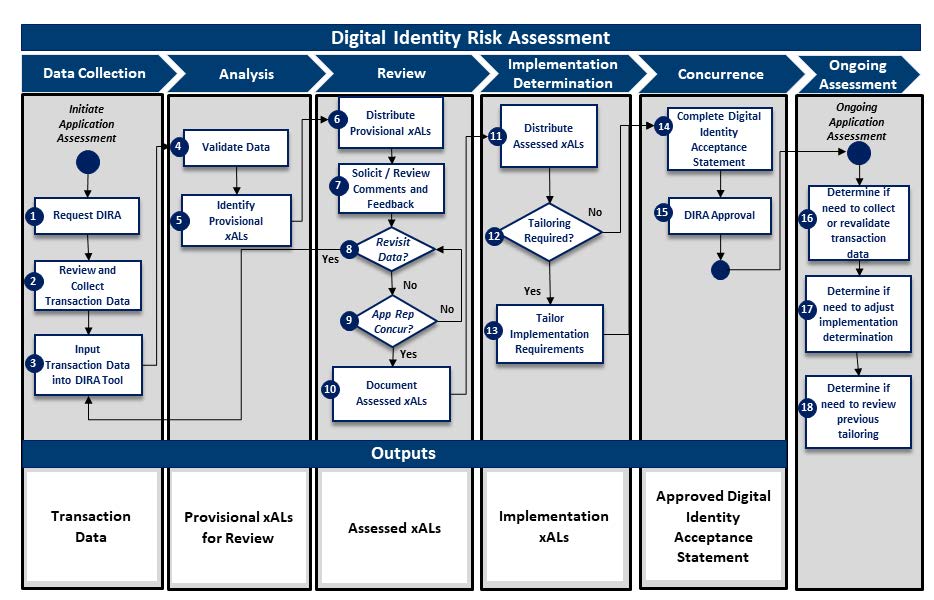

The DIRA process begins when a new online service that requires trust in the identity of the person or trust in the authenticator is identified or a time-driven or event-driven reassessment is triggered. The information identified in step 1 helps to determine the level of trust required. Once it is determined that a DIRA is needed, application data is identified, collected, and analyzed to determine the assurance levels and produce a Digital Identity Assessment Statement (DIAS), as shown in Figure 1. Using the DIAS template can help guide agencies through the DIRA process

Figure 1: Example DIRA Process

The high-level DIRA process includes five steps:

- Identify Users, Transactions, and Roles

- Identify Risks and Initial Assurance Levels

- Determine Steps to Meet Assurance Levels

- Finalize Digital Identity Assessment Statement

- Reassess

Step 1. Identify Users, Transactions, and Roles

The first step is to identify the functional scope and description of the online service, the user groups to be served, the types of online transactions that will be available, and the underlying data that the service will process through its interfaces. There are many ways to categorize users within the federal government, such as:

- User Types - Organizational and Non-Organizational users

- Communities of Users - Employee, Partner, and Public users

- Common Roles - General, Functional Privileged, and IT Privileged users

These definitions simplify complex requirements for individuals’ privacy, information security, identity, and access management.

Key Point

Identifying categories of users helps define the requirements for more than the Digital Identity Risk Assessments. For example, requirements for privacy, records retention, and monitoring are based on user types and categories.

First, identify the user types and communities of users impacted by the application . Identifying an application’s community of users is important to the DIRA processes, as communities have different privacy, regulatory, and solution requirements to consider in risk assessments. Table 1 identifies user types and five common examples of communities of users.

| User Type | Description | Examples of Community of Users |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational | An employee or individual that the organization deems to have equivalent status of an employee |

Internal agency enterprise users, including employees and direct support contractors Other federal government agency users |

| Non-organizational | All users other than organizational users (i.e., the general public or guests) |

U.S. state, local, and tribal agency users Non-profit, business, or commercial users Public or other users |

A digital transaction9 is

“… a discrete digital event between a user and a system that supports a business or programmatic purpose.”

Key Point

A government digital system may have multiple categories or types of transactions, which may require separate analysis within the overall digital identity risk assessment. Application owners and the information security team collaborate to identify, analyze, and assess the application’s digital transactions. Examples of transactions and transaction types are phrased as actions on data: Create, Read, Modify, Delete.

Finally, map the community of users to the common roles. Most applications have several different user roles, each with different access privileges and permissions. Examples of common user roles include:

- General users

- Can access: Information resources provided by the application

- Examples: Employees, the general public

- Functional privileged users

- Can access: Information resources provided by the application, and approval workflows

- Examples: Managers

- Information Technology (IT) privileged users

- Can access: IT systems with read, write, or change access

- Examples: System administrators, security analysts

Table 2 provides examples of user types, transactions, and roles.

| User Type | Community of Users | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational | Other federal government agency user | Agency employee or contractor (User Type) accesses and uploads a document to the cross-agency collaboration platform (Transaction) |

| Organizational | Internal agency enterprise user | Agency employee administrator (Role) adds user to an agency’s collaboration platform (Transaction) |

| Organizational | Internal agency enterprise user | Agency employee or contractor (User Type) exports data for use outside of the system (Transaction) |

| Organizational | Internal agency enterprise user | Agency employee supervisor (Role) approves a pending payment (Transaction) |

| Organizational | Internal agency enterprise user | Agency employee supervisor (Role) processes a payment (Transaction) |

| Non-organizational | Public user | Public user (User Type) searches for national park information and resources (Transaction) |

| Non-organizational | Public user | Public user (User Type) applies for federal government employment (Transaction) |

| Non-organizational | Public user | Public user (User Type) retrieves tax information (personally identifiable information [PII]) (Transaction) |

Step 2. Identify Risks and Assurance Levels

Determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1.

- Identity Assurance Levels (IALs) indicate robustness of the identity proofing process to determine the identity of an individual and the level of confidence in that claimed identity.

- Authentication Assurance Levels (AALs) indicate the robustness of the authentication process and the binding between an authenticator and a specific individual’s identifier. .

- Federation Assurance Levels (FALs) indicate robustness of the federation process used to communicate authentication and attribute information and the level of confidence in an assertion used to communicate identity or authentication information across applications or agencies.

The risks and impact assessment considers the risks to both the agency and the user for the transactions. The risk to one can be significant while not negatively impacting the other. It’s common for government applications to have different assurance levels based on differing impacts and risks for each community of users and transactions.

Table 3 lists the five impact categories to use. This table is a guideline for categorizing the risks and impacts to your application’s users and transactions.

| Impact Category | Low | Moderate | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degradation of mission delivery | Expected to result in limited mission capability degradation such that the organization is still able to perform its primary functions but with some reduced effectiveness. | Expected to result in serious mission capability degradation such that the organization is still able to perform its primary functions but with significantly reduced effectiveness. | Expected to result in severe or catastrophic mission capability degradation or loss over a duration such that the organization is unable to perform one or more of its primary functions. |

| Damage to trust, standing, or reputation | Expected to result in limited, short-term inconvenience, distress, or embarrassment to any party. | Expected to result in serious short-term or limited long-term inconvenience, distress, or damage to the standing or reputation of any party. | Expected to result in severe or serious long-term inconvenience, distress, or damage to the standing or reputation of any party or many individuals. |

| Unauthorized access to information | Expected to have a limited adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals as defined in FIPS 199. | Expected to have a serious adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals as defined in FIPS 199. | Expected to have a severe or catastrophic adverse effect on organizational operations, organizational assets, or individuals as defined in FIPS 199. |

| Financial loss or financial liability | Expected to result in limited financial loss or liability to any party. | Expected to result in a serious financial loss or liability to any party. | Expected to result in severe or catastrophic financial loss or liability to any party. |

| Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health | Expected to result in a limited impact on human safety or health that resolves on its own or with a minor amount of medical attention or a limited impact on environmental health that requires at most minor intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage. | Expected to result in a serious impact on human safety or health that requires significant medical attention, serious impact on environmental health that results in a period of uninhabitability and requires significant intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage, or the compounding impacts of multiple low-impact events. | Expected to result in a severe or catastrophic impact on human safety or health such as severe injury, trauma, or death, a severe or catastrophic impact on environmental health that results in long-term or permanent uninhabitability and requires extensive intervention to prevent further damage or reverse existing damage, or the compounding impacts of multiple moderate impact events. |

Identity Assurance

Identity Assurance Levels (IALs) define the processes and solutions used to identity proof users attempting to sign up for a digital service or perform an application transaction. IALs mitigate impacts of providing a benefit or information to the wrong user.

- Identity Assurance is: “Are you who you say you are?”

- Impacts are: “What are the risks to the government or to you if you aren’t?”

Defining the IALs for each community of users and transactions from Step 1 is one of the more challenging aspects of a DIRA. The initial IAL correlates to how much personal data10 is validated and verified for that user during the identity proofing process.11

If the service doesn’t require the user to have a unique digital identity or prove who they are, then there is no IAL. Identity Assurance Level 1 (IAL1) provides basic confidence that the digital identity belongs to a real person and that person is who they say they are. Core attributes are collected from identity evidence or, if the identity evidence doesn’t provide all the necessary core attributes, they may be self-asserted by the user. Identity evidence needs to be validated against authoritative or credible sources and the attributes need to be linked to the user. .. At Identity Assurance Level 2 (IAL2) or 3 (IAL3), increasingly more personal information about the user needs to be validated and verified. NIST SP 800-63A-4, Section 4 specifies the requirements for each identity assurance level.

Key Point

The risks and impacts of excessive information collection for identity proofing needs to be strongly considered for each community of users and the transactions.

For public users and other non-organizational users, privacy benefits and privacy principles are key factors to consider.

Application owners and agency processes need to include the Senior Agency Official for Privacy to define the risks, impact levels, and the Identity Assurance Levels .

Table 4 summarizes the control objectives and gives user profiles for each of the identity assurance levels:

| IAL | Control Objectives | User Profile |

|---|---|---|

| IAL1 | Limit highly scalable attacks. Protect against synthetic identity. Protect against attacks that use compromised personal information. | Access to personal information is required but limited. User actions are limited (e.g., viewing and making modifications to individual personal information). Fraud cannot be directly perpetrated through available user functions. Users cannot receive payments until an offline or manual process is conducted. |

| IAL2 | Limit scaled and targeted attacks. Protect against basic evidence falsification and theft. Protect against basic social engineering. | Users can view and change financial information (e.g., a direct deposit location). Individuals can directly perpetrate financial fraud through the available application functionality. A user can view or modify other users’ personal information. Users have visibility into or access to proprietary information. |

| IAL3 | Limit sophisticated attacks. Protect against advanced evidence falsification, theft, and repudiation. Protect against advanced social engineering attacks. | Users have direct access to multiple highly sensitive records; administrator access to servers, systems, or security data; the ability to access large sets of data that may reveal sensitive information about one or many users; or access that could result in a breach that would constitute a major incident under OMB guidance. |

Authentication Assurance

Authentication Assurance Levels indicate the strength of the authentication process and the binding between an authenticator and a specific individual’s identifier. AALs mitigate potential authentication errors (i.e., an attacker accessing a user’s account).

- Authentication Assurance is: “Is this the same user as before?”

- Impacts are: “What are the risks to the government or to you if you are not the same user as before?”

Authentication Assurance Level 1 (AAL1), provides basic confidence that the user controls the authenticator and that it’s bound to the user’s digital Identity. AAL1 only requires single-factor authentication, but multi-factor authentication options should be available and encouraged. Successful authentication requires that the claimant prove possession and control of the authenticator.

Authentication Assurance Level 2 (AAL2) provides high confidence that the user controls one or more authenticators that are bound to the user’s digital identity. AAL2 also requires at least two factors, such as a one-time password (OTP) managed by a mobile application on a personal or government mobile phone with an integrated biometric sensor that activates the phone.12

Authentication Assurance Level 3 (AAL3) provides very high confidence that the user controls the authenticators that are bound to the user’s digital identity. Authentication at AAL3 is based on proof of possession of a key through the use of a cryptographic protocol along with either an activation factor or a password. AAL3 requires the use of a hardware-based authenticator that provides phishing resistance.13

Key Point

Two-factor authentication is rapidly becoming the expected default for applications.

Recurring public and other non-organizational users may want to create an account. Agencies and application owners should always consider allowing and providing two-factor options.

For employees and other organizational government users, two-factor authentication is a government-wide policy requirement.

Table 5 summarizes the control objectives and gives user profiles for each of the authentication assurance levels:

| AAL | Control Objectives | User Profile |

|---|---|---|

| AAL1 | Provide minimal protections against attacks. Deter password-focused attacks. | No personal information is available to any users, but some profile or preference data may be retained to support usability and the customization of applications. |

| AAL2 | Require multifactor authentication. Offer phishing-resistant options. | Individual personal information can be viewed or modified by users. Limited proprietary information can be viewed by users. |

| AAL3 | Require phishing resistance and verifier compromise protections. | Highly sensitive information can be viewed or modified. Multiple proprietary records can be viewed or modified by users. Privileged user access could result in a breach that would constitute a major incident under OMB guidance. |

Federation Assurance

Federation Assurance Levels (FALs) indicate the assertion protocol used by an application to communicate identity and authenticator information. FALs protect information about the authenticated user. They mitigate risks if a malicious actor in the transaction changes or replays the information.

Key Point

Federation is an advanced topic with many different acronyms and terms.

Use outcome-based examples and demonstrations with application owners and business teams to help identify the FALs.

This playbook explains FALs with the outcomes first before explaining the high-level requirements and the risk process.14 To determine if your application requires an FAL, consider the following questions:

For existing applications and defined users and transactions (Step 1):

- Is the application integrated with any type of agency enterprise single sign-on solution?

- Is the application integrated with any government or commercial identity provider?

- For organizational government users and transactions, is the application integrated with an employee’s network logon?

For new applications and defined users and transactions (Step 1):

- Do the same users access other agency applications and could the user experience for identity and authentication be streamlined?

If your agency and application owner answers “Yes” to any of these questions, then the application is federated, or could be federated during the solution definition step (Step 3), and needs an FAL defined for each user community and transaction.

Key Point

Applications that don’t implement a federated capability document the rationale in the final Digital Identity Acceptance Statement.

FAL1 and FAL2 are good for most use cases across the federal government. Agencies and application owners should consider implementations based on the community of users and transactions.

FALs are implemented using standard-based protocols across the federal government. These protocols are commonly used in many applications and transactions globally and are routinely supported in commercial off-the-shelf (COTS), native cloud software-as-a-service, and consumer and enterprise mobile applications. Each FAL defines minimum requirements for how the integrations are performed and the requirements if the user’s information is passed between applications. For example, for some implementations, the federation assurance levels map to commonly used federation protocols such as OpenID Connect (OIDC) and Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML). How those implementations are done maps to the increasing FAL options.

FAL1 provides a basic level of protection for federation transactions and supports a wide range of use cases and deployment decisions. FAL2 provides a high level of protection for federation transactions and additional protection against a variety of attacks against federated systems, including attempts to inject assertions into a federated transaction. FAL3 provides a very high level of protection for federation transactions and establishes very high confidence that the information communicated in the federation transaction matches what was established by the credential service provider (CSP) and identity provider (IdP).

If the online service implements identity federation, an initial FAL is selected through a simple mapping process:

- Low impact: FAL1

- Moderate impact: FAL2

- High impact: FAL2 or FAL3

Table 6 summarizes the control objectives and gives user profiles for each of the federation assurance levels:

| FAL | Control Objectives | User Profile |

|---|---|---|

| FAL1 | Protect against forged assertions. | No sensitive personal information is available to any users but some profile or preference data may be retained to support usability or the customization of applications. |

| FAL2 | Protect against forged assertions and injection attacks. | Users can access personal information and other sensitive data with appropriate authentication assurance levels (e.g., AAL2 or above). |

| FAL3 | Protect against IdP compromise. | Federation primarily supports attribute exchange. Users have access to classified or highly sensitive information or services that could result in a breach that would constitute a major incident under OMB guidance. |

Key Point

The DIRA provides a minimum level and does not change established credentialing processes. For example, if a DIRA arrives at AAL2, agency leadership may decide to allow an AAL2 credential but it should not downgrade or alter an AAL3 credentialing process to AAL2.

Step 3. Determine Steps to Meet Assurance Levels

Analyze available technology and solutions at your agency, determine if they are sufficient enough to meet the application needs, and identify what you need to implement. Use data and agency enterprise defined needs when choosing solutions, including:

- Number of users by community of users;

- User experience (UX) and usability (for non-organizational users (i.e., public, business, partner)); and

- Direct and indirect benefits to reuse enterprise-level chosen solutions, including consolidated support desks.

Your agency may need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from the NIST-recommended guidance for the assessed assurance levels based on:15

- Your mission,

- Your risk tolerance,

- Your existing business processes,

- Special considerations for certain populations,

- The availability of data that provides similar mitigations to those described in the Digital Identity Guidelines, or

- Other capabilities unique to the agency.

All determinations should be documented and justified.

Step 4. Finalize Digital Identity Acceptance Statement

Formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). A DIAS must include a minimum set of information about the risk assessment and the assessed and implemented assurance levels.16

An example of a DIAS is included in Appendix B. Examples and Templates.

Step 5. Reassess

A digital identity reassessment may be time-driven or event-driven and applies to a reassessment of the DIRA. This step allows you to reevaluate and assess areas to

Key Point

Reassess digital identity risk annually or more often for higher impact categories and transactions. A time-based assessment drives alignment with modernization initiatives, changes to technology, and changes to policies.

If an event triggers a security impact analysis, an agency may perform a DIRA outside the normal continuous monitoring cycle. Significant changes requiring a digital identity reassessment include changes in:

- Core mission or business functions;

- Purpose or nature of a system;

- Risk environment;

- How information, including PII, is processed; or

- How information is processed, stored, or transmitted by the system.

Agency Process Plays

This section introduces six plays for your agency to create efficient and consistent processes for a DIRA.

Play 1. Streamline Risk Management and Assessment Processes

The Risk Management Framework (RMF) forms the basis of your agency application Assessment and Authorization (A\&A) lifecycle. A DIRA process integrates into the routine phases of the RMF to streamline processes and enables efficient reuse of application and agency resources. Figure 5 shows an alignment of this playbook’s example DIRA process steps with the RMF.

Figure 5: Example DIRA Process Steps in Risk Management Framework Phase

Step 1 of the example DIRA process happens in the Categorize phase. When categorizing a system,17 application owners and security officers identify overall system data types and assign impact levels for each of the confidentiality, integrity, and availability security objectives.

A Privacy Threshold Analysis (PTA) is typically included in this phase. The identification of the DIRA IALs, AALs, and FALs directly correlates to the collection of PII; who has access to what information; whether information is self-asserted or verified; and the risks of excessive identity proofing.

Key Point

Align Step 1 in a DIRA process with the Categorize System phase of the Risk Management Framework.

Meanwhile, Step 4 of the example DIRA process aligns with the Assessment phase. The Digital Identity Acceptance Statement must include the IALs, AALs, and FALs where the application was assessed and the implementations made.

Play 2. Add Context for the Mission

Context is powerful when assessing risks, making agency risk decisions, and engaging across multi-disciplinary agency stakeholders. Standard and general government-wide policies set the foundation for many agency activities but are written for broad mission areas. Translate user types, transactions, DIRA impact levels, and risk statements into words that are applicable and useful to your agency.

Key Point

Tailor context to your mission to support enterprise risk management discussions.

Table 4 provides examples of how agencies add agency-specific terms or context for user types, transactions, and impact levels.

| Assessment Input | Generic Definition | Definition with Agency Context |

|---|---|---|

| User Type | Organizational User | Employee or agency contractor with a federal agency email address (@agency.gov or @agency.mil) |

| User Type | Non-Organizational User | Fiscal agent, grant beneficiary, veteran, healthcare worker, or public citizen |

| Transaction | Export | Employee or agency contractors export data for use outside of the application |

| Impact Level | Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health | Impact depends on whether the application provides access to law enforcement information that identifies a confidential person (i.e., improperly disclosing a confidential person’s identity puts them in physical danger) |

| Impact Level | Degradation of mission delivery | Impact depends on the application’s function and its importance to agency operations |

| Impact Category | Scope of Potential Risk | Agency Context: As a result of a wrong user accessing data in an application, | User Type | Transaction Type | Agency Impact Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of life or danger to human safety, human health, or environmental health | Serious injury or death | Physical injury or death could occur | Organizational User | Employee or agency-contractor exports data for use outside of the system | Impact depends on whether the application provides access to law enforcement information that identifies a confidential informant (i.e., improperly disclosing a confidential criminal informant’s identity puts them in physical danger) |

| Degradation of mission delivery | Adverse effect on organizational operations | The agency’s mission essential functions is adversely impacted | Non-Organizational User | Individual retrieves tax information (PII) | Impact depends on the application’s function and its importance to agency operations |

Play 3. Use Templates

It’s a best practice that agencies develop standardized templates to promote consistency in procedures for digital identity risk assessments. Example templates can be as simple as:

- Visual informational guides for what a DIRA is,

- Informational guides on risks,

- Simple spreadsheets or digital surveys, and

- Digital Identity Acceptance Statements.

Appendix B. Examples and Templates contains a few example templates provided by agencies.

Play 4. Shortcut Decision Guides

All federal applications that perform digital transactions and require identity proofing or authentication require a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement, regardless of how the system is hosted. However, not all federal applications require the full example DIRA process and efforts.

Table 6 provides an example shortcut guide for determining whether to perform a full DIRA process based on application characteristics. IAL, AAL, and FAL levels in this table are examples. Applications must follow agency policies, which may be more stringent than the examples in this table.

| Application Characteristics | DIRA Required? | Minimum NIST SP 800-63 IAL, AAL, FAL Levels |

|---|---|---|

| The application has no external network connectivity, is physically isolated, and is located in a protected space. | No | N/A |

| The application leverages the agency enterprise single sign on (SSO)/enterprise access manager for authentication of employees and contractors. | Yes | Requires proof of identity (IAL3).18 Multi-factor authentication to agency application (AAL2) federation between agency applications (FAL2). Additionally, requires affiliation as a federal employee or contractor. |

Data and other resources available are approved for public release, are intended to be freely shared, and public users aren’t required to create accounts to access this information. Examples include:

|

No | Public users don't create accounts or login. Agency-affiliated privileged users with permissions to edit content still require higher IAL and a minimum AAL2 (two-factor). |

| Data and other resources are intended for public release. Doesn't include any controlled unclassified information, but allows public users to create accounts to better support the public user’s experience. | Yes | Doesn't require proof of a real-life identity (No IAL). Single or multi-factor authentication (AAL1). |

| Allows public users to input and access their own personally identifiable information (PII) or protected health information (PHI) for informational purposes. The information isn’t required to be verified. The application doesn’t allow public users to access anyone else’s PII or PHI. | Yes | Doesn't require proof of a real-life identity (No IAL). Multi-factor authentication (AAL2). |

Play 5. Leverage Existing Agency Tools

Leverage existing tools at your agency to automate and create repeatable and consistent DIRA processes. For example, one agency integrated the DIRA process into its Governance Risk and Compliance (GRC) tool. The agency was able to simplify integration with the Risk Management Framework (RMF) lifecycle and support the inclusion of the DIAS with other system artifacts. Agencies that use commercial GRC tools should consider integrating DIRAs into the workflows.

There are an increasing number of AI-driven tools entering the market that can help to facilitate the DIRA process. For example, AI- powered Identity verification and fraud prevention tools can help reduce overall identity risks and streamline many different on-boarding processes.

Play 6. Less Is More

A common assumption when building or buying applications for missions is that all users need accounts. Take the opportunity during the DIRA process to consider the application processes and functionality needed. Consider the mission, applications needs, and the two example questions below:

- Do all users need accounts?

- How many users are regularly recurring returning users?

Reconsider the business process carefully and validate the current and future designs using data on the returning users, transaction volumes, and privacy principles.

- Design the business process for the user to submit information without requiring an account,

- Limit the information required to create the account, and

- Make most of the information requested optional.

Key Point

Some public, business, or partner users may only interact with the government process and application once a year or less.

Revisit your process and application, and allow users to complete the transaction once before opting in to create an account.

Appendix A. Policy, Standards, and Guidance

This section provides links to the federal laws, policies, standards and other guidance that impact and shape DIRA implementations. NIST also publishes useful Frequently Asked Questions for agencies, and Implementation Resources for solution developers.

| Short Name | Full Name and Publication Date |

|---|---|

| NIST SP 800-63-4 | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-63-4; Digital Identity Guidelines, June 22, 2017 |

| NIST SP 800-63A-4 | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-63A-4; Digital Identity Guidelines: Enrollment and Identity Proofing, June 22, 2017 |

| NIST SP 800-63B-4 | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-63B-4; Digital Identity Guidelines: Authentication and Lifecycle Management, June 2017 |

| NIST SP 800-63C-4 | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-63C-4; Digital Identity Guidelines: Federation and Assertions, June 22, 2017 |

| FISMA | Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014, 44 U.S.C. § 3551 et seq., Public Law (P.L.) 113-283, December 8, 2014 |

| HSPD-12 | Department of Homeland Security, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12: Policy for a Common Identification Standard for Federal Employees and Contractors, August 27, 2004 |

| EO 13681 | Executive Order 13681, Improving the Security of Consumer Financial Transactions, October 2014 |

| EO 13800 | Executive Order 13800, Strengthening the Cybersecurity of Federal Networks and Critical Infrastructure, May 2017 |

| A-130 | OMB Circular A-130, Managing Federal Information as a Strategic Resource, July 28, 2016 |

| A-108 | OMB Circular A-108, Federal Agency Responsibilities for Review, Reporting, and Publication under the Privacy Act, December 2016 |

| A-123 | OMB Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, July 15, 2016 |

| M-19-17 | OMB M-19-17, Enabling Mission Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management, May 21, 2019 |

| FIPS 199 | NIST FIPS Publication 199, Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems, February 2004 |

| NIST SP 800-37 | NIST Special Publication 800-37, Revision 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy, December 2018 |

| NIST SP 800-53 Rev. 5 | NIST Special Publication 800-53, Revision 5, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations, Updated September 2020 |

| NIST SP 800-53A Rev. 5 | NIST Special Publication 800-53A, Revision 5, Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Information Systems and Organizations, Updated January 2022 |

| NIST RMF Overview | NIST Risk Management Framework Overview, November 30, 2016 |

Appendix B. Examples and Templates

This appendix provides examples and templates of existing resources to help establish or improve DIRA processes. It includes the following sections:

- Process Flow Examples

- Digital Identity Acceptance Statement Example and Template

1. Process Flow Examples

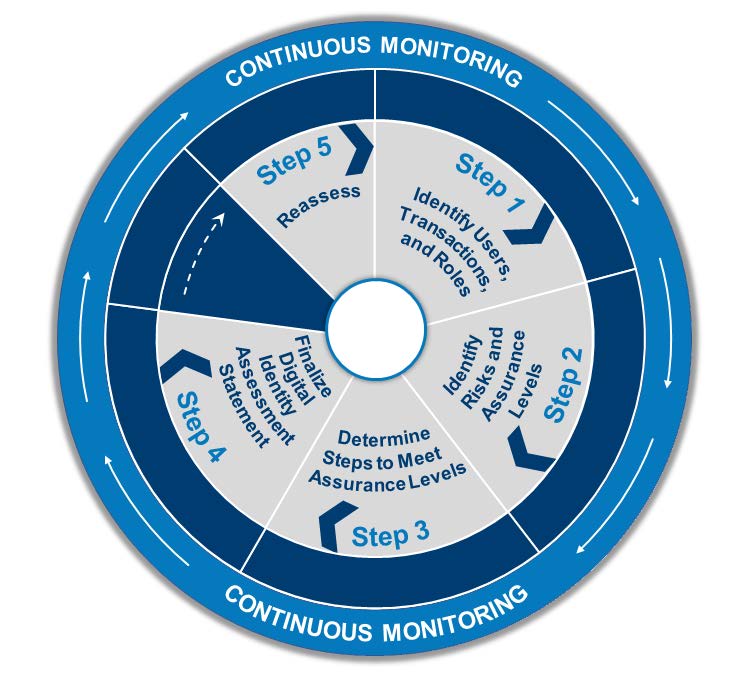

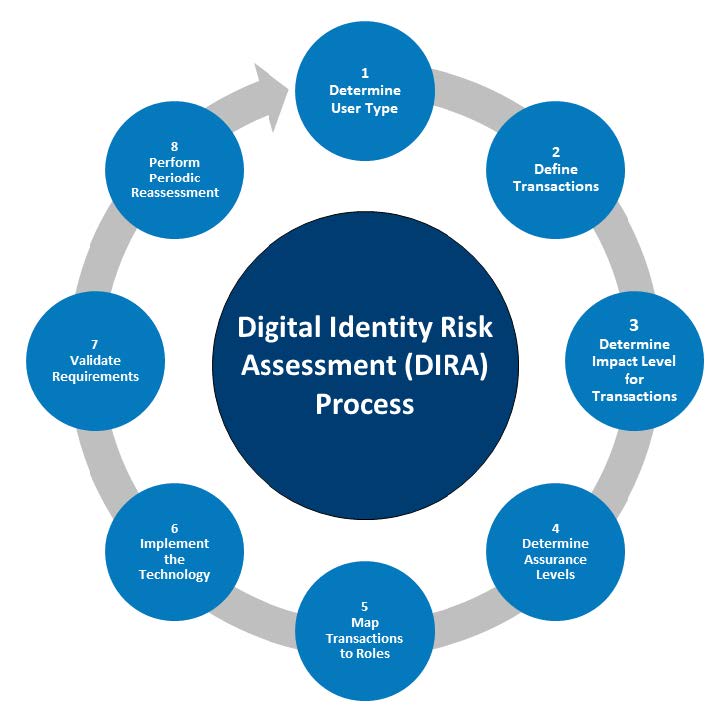

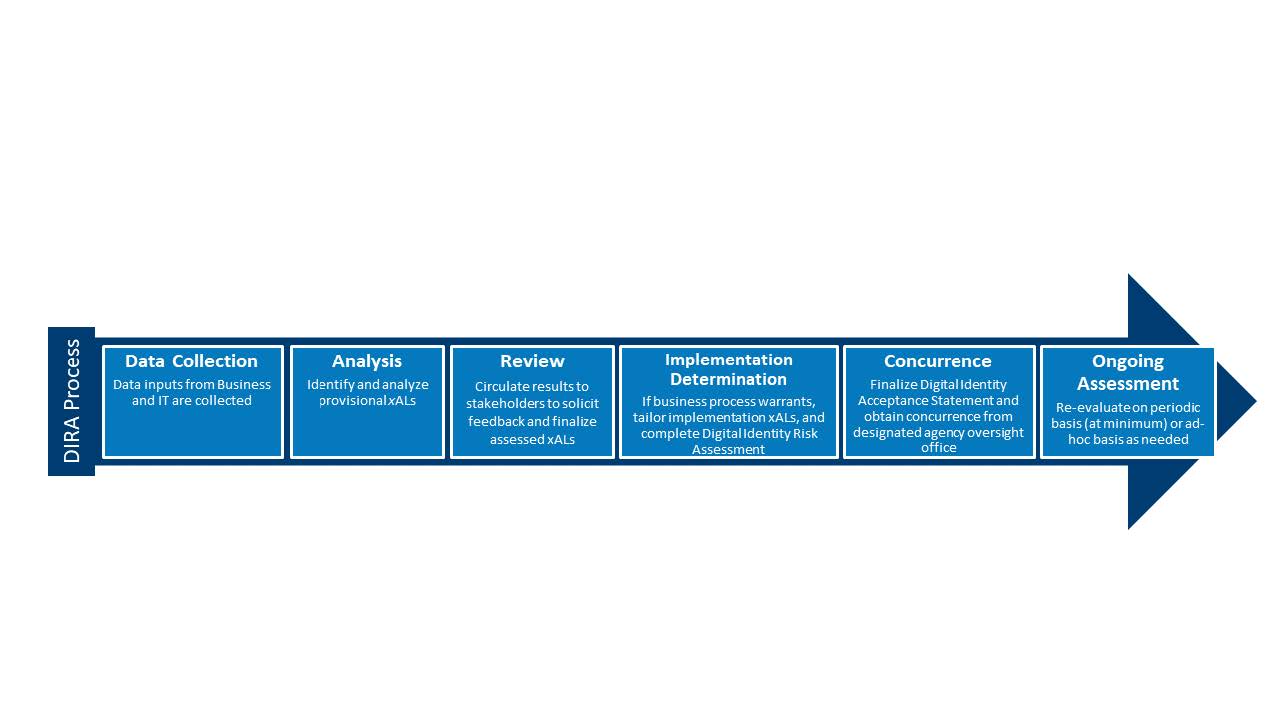

This section includes example process flow diagrams used by some agencies for the Digital Identity Risk Assessment processes. Choose and reuse any process flow that works best for your agency.

Figure 9: The DIRA Process from Data Collection to Ongoing Assessment

Figure 10: Describes the DIRA Process Flow from the Data Collection Phase to the Ongoing Assessment Phase

Figure 11: A Six-Step Process of What is Required to Implement a DIRA

2. Digital Identity Acceptance Statement Example Template

This Digital Identity Acceptance Statement template is provided as an example for agencies to use or modify as needed

Appendix C. NIST Special Publication 800-63-4, Requirements Traceability Matrix

This appendix includes both normative requirements and informative references from NIST SP 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines. Only requirements related to the agency processes for digital identity risk assessments are included. The Playbook Consideration column includes comments on the standards statements and alignment to this playbook’s development.

| Requirement | Section | Playbook Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Federal RPs SHALL implement the DIRM process for all online services. | 3 | This supports the assertion that federal agencies should apply the DIRA process to their online services. |

| At a minimum, organizations SHALL execute and document each step and complete and document the normative mandates and outcomes of each step, regardless of any organization-specific processes or tools used in the overall DIRM process. | 3 | This supports the documentation of the DIRA process in a DIAS. |

RPs SHALL develop a description of the online service that includes, at minimum:

|

3.1 | Supports Step 1 of the DIRA process to identify the functional scope and description of the online service, the user groups to be served, the types of online transactions that will be available, and the underlying data that the service will process through its interfaces. |

| The scope of impact assessments SHALL include individuals who use the online application as well as the organization itself. | 3.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the impacts by the community of users. |

| Organizations SHALL document all impacted entities (both internal and external to the organization) when conducting their impact assessments. | 3.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users. |

The impact assessment SHALL include:

|

3.2 | Supports Step 2 recommendation to determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1. |

| The level of impact for each user group identified in Sec. 3.1 SHALL be considered separately based on the transactions available to that user group. | 3.2 | Supports Step 2 recommendation to determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1. |

| While impacts to user groups, the organization, and other entities are primary considerations for impact assessments, organizations SHOULD also consider scale (e.g., number of persons impacted by transactions). | 3.2 | Supports Step 2 recommendation to determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1. |

At a minimum, organizations SHALL include the following impact categories in their impact assessments:

|

3.2.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users for the transactions. |

| Organizations SHOULD include additional impact categories, as appropriate, based on their mission and business objectives. Each impact category SHALL be documented and consistently applied when implementing the DIRM process across different online services offered by the organization. | 3.2.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users for the transactions. |

| For each impact category, organizations SHALL consider potential harms for each of the impacted entities identified in Sec. 3.1. | 3.2.1 | Supports Step 2 recommendation to determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1. |

| To provide a more objective basis for impact level assignments, organizations SHOULD develop thresholds and examples for the impact levels for each impact category. Where this is done, particularly with specifically defined quantifiable values, these thresholds SHALL be documented and used consistently in the DIRM assessments across an organization to allow for a common understanding of risks. | 3.2.2 | Supports Step 2 recommendation to determine the digital identity risk for each assurance category by assessing the impacts for each community of user, user type, common role, and transactions identified in Step 1. |

| The impact analysis SHALL consider the level of impact for each impact category for each type of impacted entity if an intruder obtains unauthorized access as a member of each user group. Because different sets of transactions are available to each user group, it is important to consider each user group separately for this analysis. | 3.2.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users for the transactions. |

| The impact analysis SHALL be performed for each user group that has access to the online service. | 3.2.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users for the transactions. |

| The output of this impact analysis is a set of impact levels for each user group that SHALL be documented in a suitable format for further analysis in accordance with Sec. 3.4. | 3.2.3 | Supports Step 4, to formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). |

| Organizations SHALL document the approach they use to combine their impact assessment into an overall impact level for each of their defined user groups and SHALL apply it consistently across all of its online services. At the conclusion of the combinatorial analysis, organizations SHALL document the impact for each user group. | 3.2.4 | Supports the proposed process recommendations for the risks and impact assessments to consider both the agency and the users for the transactions. |

The RP SHALL identify the types of assurance levels that apply to their online service from the following:

|

3.3.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| Organizations SHALL develop and document a process and governance model for selecting initial assurance levels and controls based on the potential impacts of failures in the digital identity system. | 3.3.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| The organization SHALL document whether identity proofing is required for their application and, if it is, SHALL select an initial IAL for each user group based on the effective impact level determination from Sec. 3.2.4. | 3.3.3.1 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| The organization SHALL document whether authentication is needed for their online service and, if it is, SHALL select an initial AAL for each user group based on the effective impact level determination from Sec. 3.2.4. | 3.3.3.2 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| Consistent with M-19-17, federal agencies that operate online services SHOULD implement federation as an option for user access. | 3.3.3.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| The organization SHALL document whether federation will be used for their online service and, if it is, SHALL select an initial FAL for each user group based on the effective impact level determination from Sec. 3.2.4. | 3.3.3.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

| For online services that are assessed to be high impact, organizations SHALL conduct a further assessment to evaluate the risk of a compromised IdP to determine whether FAL2 or FAL3 is more appropriate for their use case. Considerations SHOULD include the type of data being accessed, the location of the IdP (e.g., whether the IdP is internal or external to their enterprise boundary), and the availability of bound authenticators or holder-of-key capabilities. | 3.3.3.3 | Supports the proposed process recommendations to independently assess the assurance levels by the community of users and transactions. |

|

Using the initial xALs selected in Sec. 3.3.3, the organization SHALL identify the applicable baseline controls for each user group as follows:

|

3.3.4 | Supports Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| Within the tailoring step, organizations SHALL focus on impacts to mission delivery due to the implementation of identity management controls, including the possibility of legitimate users who are unable to access desired online services or experience sufficient friction or frustration with the identity system (and technology selection) that they abandon attempts to access the online service. | 3.4 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| As a part of the tailoring process, organizations SHALL review the Digital Identity Acceptance Statements and practice statements[^Practice] from CSPs and IdPs that they use or intend to use. However, organizations SHALL also conduct their own analysis to ensure that the organization's specific mission and the communities being served by the online service are given due consideration for tailoring purposes. As a result, the organization MAYrequire their chosen CSP to strengthen or provide optionality in the implementation of certain controls to address risks and unintended impacts to the organization's mission and the communities served. | 3.4 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

Organizations SHALL establish and document their xAL tailoring process. At a minimum, this process:

|

3.4 | Supports the assertion that all determinations should be documented and justified. |

| When progressing from the initial assurance level selection in Sec. 3.3.4 to the final xAL selection and implementation, organizations SHALL conduct detailed assessments of the controls defined for the initially selected xALs to identify potential impacts in the operational environment. | 3.4.1 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

At a minimum, organizations SHALL assess the impacts and potential unintended consequences related to the following areas:

|

3.4.1 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| All assessments applied during the tailoring phase SHALL be extended to any compensating or supplemental controls, as defined in Sec. 3.4.2 and Sec. 3.4.3. | 3.4.1 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| Any cost-based decisions that result in modifications to assessed xALs or baseline controls SHALL be documented in the Digital Identity Acceptance Statement | 3.4.1 | Supports Step 4, to formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). |

| Organizations MAYchoose to implement a compensating control if they are unable to implement a baseline control or when a risk assessment indicates that a compensating control sufficiently mitigates risk in alignment with organizational risk tolerance. This control MAYbe a modification to the normative statements defined in these guidelines or MAYbe applied elsewhere in an online service, digital transaction, or service life cycle. | 3.4.2 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| Where compensating controls are implemented, organizations SHALL document the compensating control, the rationale for the deviation, comparability of the chosen alternative, and any resulting residual risks. | 3.4.2 | Supports the assertion that all determinations should be documented and justified. |

| Organizations SHOULD identify and implement supplemental controls to address specific threats in the operational environment that may not be addressed by the baseline controls. | 3.4.3 | Supports the proposed need to tailor the initial assurance levels and baseline controls from Step 3 of the DIRA process. |

| Any supplemental controls SHALL be assessed for impacts based on the same factors used to tailor the organization's assurance level and SHALL be documented. | 3.4.3 | Supports the assertion that all determinations should be documented and justified. |

| Organizations SHALL develop a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS) to document the results of the DIRM process for (i) each online service managed by the organization, and (ii) each external online service used to support the mission of the organization, including software-as-a-service offerings (e.g., social media platforms, email services, online marketing services). | 3.4.4 | Supports Step 4, to formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). |

| RPs who intend to use a particular CSP/IdP SHALL review the latter's DIAS and incorporate relevant information into the organization's DIAS for each online service. | 3.4.4 | Supports Step 4, to formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). |

Organizations SHALL prepare a DIAS for their online service that includes, at a minimum:

|

3.4.4 | Supports Step 4, to formalize the results of the assessment process with a Digital Identity Acceptance Statement (DIAS). |

| Federal agencies SHOULD include this information in the information system authorization package described in the NIST RMF. | 3.4.4 | Supports the proposed DIRA process step recommendations to align with the Risk Management Framework and SA&A of IT systems. |

| Organizations SHALL implement a continuous evaluation and improvement program that leverages input from end users who have interacted with the identity management system as well as performance metrics for the online service. | 3.5 | Supports Step 5 of the DIRA process to periodically reassess the findings of the DIRA for gaps and areas needing improvement. |

| This program SHALL be documented, including the metrics that are collected, the sources of data required to enable performance evaluation, and the processes in place for taking timely actions based on the continuous improvement process. | 3.5 | Supports Step 5 of the DIRA process to periodically reassess the findings of the DIRA for gaps and areas needing improvement. |

| Organizations SHALL regularly assess the effectiveness of current security measures and fraud detection capabilities against the latest threats and fraud tactics. | 3.5 | Supports Step 5 of the DIRA process to periodically reassess the findings of the DIRA for gaps and areas needing improvement. |

To fully understand the performance of their identity system, organizations will need to identify critical inputs to their continuous evaluation process. At a minimum, these inputs SHALL include:

|

3.5.1 | Supports Step 5 of the DIRA process to periodically reassess the findings of the DIRA for gaps and areas needing improvement. |

| RPs SHALL document their metrics, reporting requirements, and data inputs for any CSP, IdP, or other integrated identity service to ensure that expectations are appropriately communicated to partners and vendors. | 3.5.1 | Supports Step 5 of the DIRA process to periodically reassess the findings of the DIRA for gaps and areas needing improvement. |

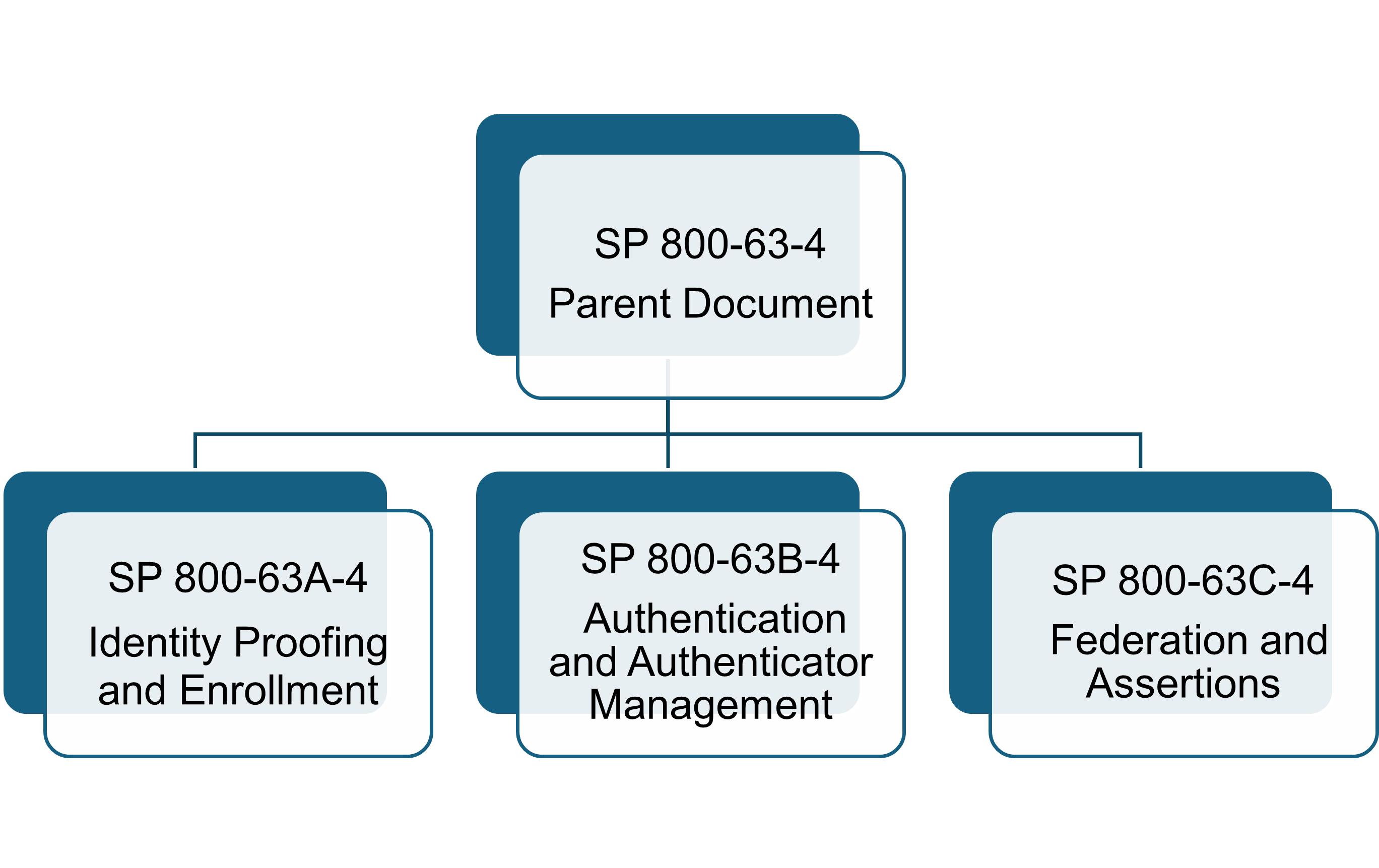

Appendix D. Updates to NIST Special Publication 800-63

In June 2017, NIST replaced SP 800-63-2,Electronic Authentication Guideline,with SP 800-63-3, Digital Identity Guidelines. The new standard provided agencies with increased security and privacy, more flexibility to meet their mission and constituent needs, and better alignment with digital identity best practices. In 2025, NIST updated SP 800-63-3 with SP 800-63-4. This update expanded security, privacy, and customer experience considerations, updated the digital identity models to include a user-controlled wallet federation model that addresses the increased attention and adoption of digital wallets, and streamlined the digital identity risk management process.NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines identify the implementation requirements for conducting a DIRA and enable modernized risk-driven approaches for digital identities. Figure 12 depicts updated content details.

Figure 12: Digital Identity Guideline Information Locations

- The SP 800-63-4 parent document outlines the digital identity risk assessment methodology that federal agencies must implement. The other three documents address the three assurance level categories: Identity Assurance Level (IAL), Authentication Assurance Level (AAL), and Federation Assurance Level (FAL). These three assurance levels are known collectively as xALs.

Mix and Match xALs

The xALs in the revised guidance can be mixed and matched, giving agencies the flexibility to deploy strong authentication without having to prove a user’s identity (i.e., if the collection of sensitive information is not required). The mix and match assurance levels allow opportunities for:

- Greater flexibility,

- Greater user experience,

- Enhanced privacy, and

- Reduced risk.

Footnotes

- A digital service is any federal Information Technology (IT) system or application accessible over the public internet or agency intranet. ↩

- A Digital Identity Risk Assessment is a method of applying Digital Identity Risk Management required by OMB Memorandum 19-17: Enabling Mission Delivery through Improved Identity, Credential, and Access Management, and described in NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines. ↩

- For more information, refer to NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines. ↩

- NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Frequently Asked Questions. ↩

- Pursuant to 0MB Circular A-130, “information system” means a discrete set of information resources organized for the collection, processing, maintenance, use, sharing, dissemination, or disposition of information. System and application are used synonymously throughout this playbook. ↩

- Refer to NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Section 1.1, Scope and Applicability. ↩

- The working group members determined Federation Assurance Level 3 was complex and not widely supported in commercial products and implementations. The working group decided the Federation Assurance Level 3 explanations were better served by agency technical exchanges or deferred to details included in NIST Special Publications. ↩

- Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014, 44 U.S.C. § 3551 et seq., Public Law (P.L.) 113-283, December 8, 2014. ↩

- Refer to NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Appendix B, Glossary. ↩

- Personal data is personally identifiable information (PII). As defined by OMB Circular A-130, PII is information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, either alone or when combined with other information that is linked or linkable to a specific individual. ↩

- Agencies collecting identity information as part of identity proofing may be subject to specific retention policies in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, or policies, including any National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) records retention schedules. ↩

- Examples only. Refer to NIST Special Publication 800-63B-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Authentication and Authenticator Management. Section 2.2 Authentication Assurance Level 2.↩

- Refer to NIST Special Publication 800-63B-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Authentication and Authenticator Management. Section 2.3 Authentication Assurance Level 3. ↩

- See NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Section 2.4, Federation and Assertions. ↩

- NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Section 3.4, Tailor and Document Assurance Levels. ↩

- NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 Digital Identity Guidelines, Section 3.4.4, Digital Identity Acceptance Statement. ↩

- Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 199 (FIPS 199) Standards for Security Categorization of Federal Information and Information Systems, Section 3, Categorization of Information and Information Systems (page 1). ↩

- Satisfied by the full PIV issuance processes, in accordance with government-wide policy and Office of Personnel Management (OPM) credentialing requirements for federal executive branch employees and contractors. ↩