Phishing-Resistant Authenticator Playbook

The Fast IDentity Online 2 Community of Action, along with content developed by the ICAM Subcommittee Phishing Resistant Authenticator Working Group and a brainstorming session at the October 2023 FIDO Authenticate conference, developed this playbook to help agencies understand phishing-resistant authentication and plan a phishing-resistant authenticator pilot. This playbook will be updated as the standards and specifications evolve and more forms of phishing-resistant authenticators are identified.

In collaboration with the FIDO2 CoA members, the FIDO Alliance also published a sister publication on more FIDO-specific areas. See the FIDO White Paper on FIDO Alliance Guidance for U.S. Government Agency Deployment of FIDO Authentication for more information.

| Version Number | Date | Change Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 02/22/2024 | Clarified passkey, added FIDO attestation example, added pilot criteria, and examples in lifecycle. See Issue 798. |

| 1.0 | 02/15/2024 | Initial draft. |

Executive Summary

This Phishing-Resistant Authenticator Playbook is a practical guide to help agencies understand and implement multiple types of phishing-resistant authentication. Office of Management and Budget Memo 22-09, Federal Zero Trust Strategy, provides ongoing guidance for modernizing Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 for logical IT access. M-22-09 outlines that Agencies must require their users, including employees, contractors, and other workforce users such as mission and business partners, to use a phishing-resistant method to access agency resources. This includes removing any authentication option that fails to resist credential-based attacks, such as phishing, push bombing, SIM swap, and adversary-in-the-middle One-Time PIN (OTP) interception. These phishable and replayable authentication options used by most agencies include SMS or voice one-time pins (OTP), Time-based OTP (TOTP) for mobile, email, and tokens, or mobile application push notifications. Only phishing-resistant authentication options reduce an agency’s risk associated with credential-based attacks, often leading to account compromise and network/cloud lateral movement.

Almost all federal executive branch agencies leverage the HSPD 12 Personal Identity Verification (PIV) smart card to meet this requirement as a primary authenticator. However, circumstances and user types exist where someone cannot access a PIV smart card. In these circumstances, Agencies fall back to using other authenticators, including Derived PIV and PIV-Interoperable, but more so those authenticators susceptible to credential-based attacks because they are an easy and available option in almost all cloud-based access management platforms. For a good reason: any MFA authentication option is better than just a password alone, but phishing-resistant authentication options are widely available on many modern devices, browsers, and platforms. Agencies should support multiple types of phishing-resistant authentication to reduce the risk of account takeover and support a more remote and technological workforce. These circumstances and user types include:

- An alternative option based on access type, such as supporting personal devices or web applications.

- A backup authentication option for account recovery that doesn’t rely on passwords or email-based codes.

- Employees or contractors who’ve completed a suitability determination and are waiting for their PIV credential to be issued but can start work.

- Short-term employees and other workforce users, such as mission and business partners, who do not meet the OPM credentialing requirements for PIV eligibility.

- An option for public users to secure their benefits, payment, or other accounts.

From a policy and compliance perspective, HSPD-12 states agencies must implement the PIV standard, Federal Information Processing Standard 201, to the maximum extent possible. However, “Departments and agencies shall implement this directive in a manner consistent with ongoing Government-wide activities, policies and guidance issued by OMB, which shall ensure compliance.” While OMB M-22-09 does not explicitly override HSPD-12, it sets a path forward for ongoing guidance and compliance for logical authentication (e.g., accessing IT systems). It modernizes the HSPD-12 intent to be flexible through adopting new technologies, meeting changing needs, and shifting focus from the credential lifecycle to the identity lifecycle as outlined in OMB Memo 19-17. This shift implements a more inclusive approach to authenticator options, emphasizing multiple phishing-resistant MFA methods. M-22-09 reinforces the requirement of PIV authentication for federal employees and contractors while acknowledging that FIDO2, Web Authentication-based authenticators, and other non-PKI authenticators can meet the new MFA requirements. Compliance requirements are also updated through quarterly FISMA metric collection and updated NIST Special Publication 800-53 security controls. Therefore, while HSPD-12 establishes PIV authentication as the government-wide standard, M-22-09 acknowledges that the PIV smart card format may not be practical in all scenarios and permits agencies to leverage other phishing-resistant alternative authenticators for logical access to federal IT systems. These alternative options are comparable in PIV authentication strength and natively built into modern devices, platforms, and browsers.

This playbook includes three sections.

- an educational 101 section,

- a three-step process to help agencies identify use cases and technical solutions and

- an outline of a phishing-resistant authentication pilot plan.

The pilot plan is derived from experiences shared during the FIDO2 CoA and content developed by the ICAM Subcommittee Phishing Resistant Authenticator Working Group. The three-step pilot process includes the following:

- Recognize common authentication patterns and use cases to scope a pilot.

- Identify available solutions or acquisition strategies.

- Deploy a pilot using the FIDO2 CoA six-part pilot plan.

Pursue Greater use of Passwordless Multi-factor Authentication

When a PIV credential is impractical, the Federal Zero Trust Strategy, OMB Memo 22-09, permits agencies to use alternative, phishing-resistant authenticators such as FIDO2 and Web Authentication. The Strategy also encourages agencies to pursue greater use of passwordless technology for their workforce and public users.

Key Terms

These are key terms used throughout this playbook. A linked term denotes an official term from a federal policy, a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) glossary, or a NIST publication. An unlinked term is defined for this playbook.

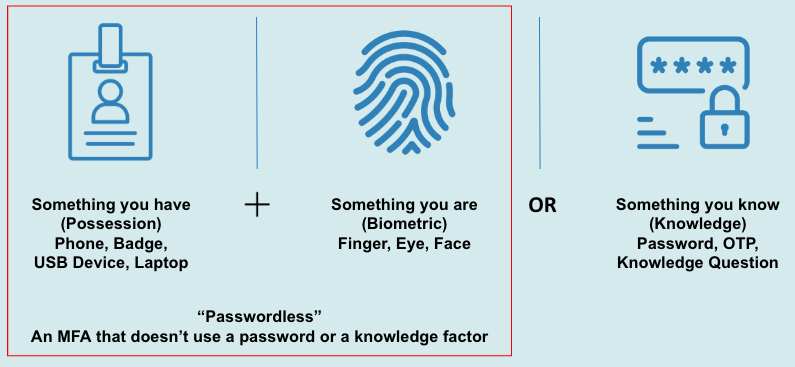

- Authentication Factor - The three types of authentication factors are something you know, something you have, and something you are. Every authenticator has one or more authentication factors.

- Authenticator - Something the claimant possesses and controls (typically a cryptographic module or password) that is used to authenticate the claimant’s identity.

- Certificate-Based Authentication - A type of phishing-resistant authentication that leverages a digital certificate such as a PIV authentication certificate or other types of digital certificates.

- Credential - An object or data structure that authoritatively binds an identity - via an identifier or identifiers - and (optionally) additional attributes, to at least one authenticator possessed and controlled by a subscriber.

- Derived PIV (DPIV) Credential — A credential issued based on proof of possession and control of a PIV Card. Derived PIV credentials are typically used in situations that do not easily accommodate a PIV Card, such as in conjunction with mobile devices.

- Fast IDentity Online (FIDO) 2 - FIDO2 is a FIDO specification, Client-to-Authenticator Protocol (CTAP), and a World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standard, Web Authentication (WebAuthn). FIDO2 is backward compatible with its predecessor, FIDO Universal 2nd Factor (U2F).

- FIDO Certification - A vendor product is found compliant through an authorized FIDO testing center or event with the FIDO Universal Authentication Framework (UAF), Universal 2 Factor (U2F), or FIDO2 specification and listed on the FIDO Certified website.

- FIDO Passkey (Discoverable Credential) - The high level, end-user centric term for a FIDO2/WebAuthn Discoverable Credential. Like “password”, “passkey” is a common noun intended to be used in everyday conversations and experiences. Passkeys can be either synced or device-bound.

- FIDO Platform Authenticator - A hardware-based authenticator built into a device such as a laptop, tablet, or smartphone that implements the FIDO2 specification in an authenticator that is embedded in the device, typically in a restricted execution environment in that device. Some FIDO platform authenticators may also double as a FIDO Passkey, but are not exportable.

- FIDO Roaming Authenticator - A hardware-based security key that can connect to a client device via USB or NFC. They may also take other forms, such as a smart card, or be a component of a device like a smartphone.

- Multi-factor Authentication (MFA) - An authentication system that requires more than one distinct authentication factor for successful authentication.

- Only Locally Trusted (OLT) - A Public Key Infrastructure used internally by an organization and not trusted outside a security boundary. Examples of an OLT PKI are Active Directory Certificate Services for domain controllers.

- Phishing - A technique for attempting to acquire sensitive data, such as bank account numbers, through a fraudulent solicitation in email or on a web site, in which the perpetrator masquerades as a legitimate business or reputable person.

- Phishing-resistant Authentication - Authentication processes designed to detect and prevent disclosure of authentication secrets and outputs to a website or application masquerading as a legitimate system. In 800-63-3, this aligns with verifier impersonation resistance or highly resistant to Man in the Middle attacks.

- PIV Credential - A credential that authoritatively binds an identity (and, optionally, additional attributes) to the authenticated cardholder that is issued, managed, and used in accordance with the PIV standards. These credentials include public key certificates stored on a PIV Card as well as other authenticators bound to a PIV identity account as derived PIV credentials.

- PIV-Interoperable (PIV-I) Credential - An identity credential that is conformant with the Federal Government PIV Standards for identity assurance and authenticator assurance but asserts no personnel vetting assurance in a baseline, standardized manner.

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM) - A tamper-resistant integrated circuit built into some computer motherboards that can perform cryptographic operations (including key generation) and protect small amounts of sensitive information, such as passwords and cryptographic keys.

- Verifier - An entity that verifies the claimant’s identity by verifying the claimant’s possession and control of one or two authenticators using an authentication protocol. To do this, the verifier may also need to validate credentials that link the authenticator(s) to the subscriber’s identifier and check their status.

- Verifier Impersonation Resistance - A scenario where the attacker impersonates the verifier in an authentication protocol, usually to capture information that can be used to masquerade as a subscriber to the real verifier.

- Workforce Identity - Using identity, credential, and access management capabilities to provide employees and other internal users, such as contractors and partners, secure access to organization-owned resources.

Audience

This playbook is designed to assist agency ICAM program managers, enterprise, and application architects in reducing or replacing passwords in their agency or applications with phishing-resistant authentication methods. IT program participants, including program managers and application teams, may find value in incorporating this playbook in their technology implementation planning.

Disclaimer

U.S. Federal Executive Branch agencies can use this playbook to plan and integrate phishing-resistant authenticators into their agency’s ICAM processes. This playbook is not an official policy, does not mandate an agency action, nor does it provide authoritative information technology terms. It includes best practices to supplement existing federal policies and builds upon OMB Memorandum 22-09, 19-17, and existing FICAM guidance and playbooks. Subject areas with intersecting scopes, such as identity proofing, lifecycle management, authenticator binding, credentialing standards, and authenticator assurance levels, are considered only to the extent they relate to identifying and implementing phishing-resistant authentication. Privileged access management (e.g., superusers, domain administrators) is out of the scope of this playbook.

This playbook will be updated when NIST Special Publication 800-63-4 and 800-157-1 is published.

FIDO2 Community of Action

To help support agencies aggressively replace passwords and other phishable authenticators, the OMB, the Department of Homeland Security Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency, and the ICAM Subcommittee established the FIDO2 CoA. A CoA has three distinct characteristics and differs from a Community of Practice.

- Short-term, usually six months.

- Small group, usually 4-8 agencies.

- Actively piloting a solution, sharing challenges and lessons learned.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

The FIDO2 CoA completed two cohorts, which included eight agencies that either piloted a solution or evolved a pilot to their entire production community. The pilots included a combination of platform authenticators like Windows Hello for Business and roaming authenticators like Yubico Yubikey and RSA DS-100.

Challenges

- Compliance Mentality - Some organizations take a strict compliance approach to only use PIV or Derived PIV credentials because this is the only “Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 approved credential” with the mentality that when a PIV-based credential is unavailable, relying on a time-boxed access exception policy leveraging a password is acceptable until the user has a PIV credential. This mentality is inaccurate and grounded in rescinded OMB memos and deprecated FISMA metrics. While agencies must continue to follow the OPM credentialing policy to complete a suitability determination, agencies have multiple options to meet the FISMA MFA requirement for logical access. OMB Memo 22-09, updated FISMA metrics, and NIST 800-53 security controls allow an agency to use other types of phishing-resistant authenticators and not rely solely on a PIV credential. The decision to use any authenticator is dependent on an individual organization’s risk appetite, security control tailoring, and data security.

- Inconsistent user experience - Although FIDO2 is a specification, vendors can introduce their variations and brands (e.g., the Apple platform authenticator is Face ID, while Android doesn’t have a branded name). These small variations can lead to an inconsistent user experience when working in multi-device, multi-operating systems and multi-browser environments. Follow the guidance in this playbook to test across all organization-supported operating systems and browsers and document the process to publish as user stories during your authenticator adoption campaigns. This type of vendor branding is not unique either. The Federal PIV-I credential also has a similar challenge in how vendors decide to make a PIV-I visually distinct from a PIV.

- Registration and account recovery continue to be an attack vector - The initial onboarding of an individual is either in-person or through a remote authentication process leveraging a lower assurance authenticator, such as enrolling an email for an OTP to associate a higher assurance authenticator like a phishing-resistant authenticator. Account recovery is the organizational process for users to recover access to their account using a backup authenticator when their primary authenticator is locked, forgotten, or unavailable. An organization’s account recovery process often relies on a lower assurance authenticator, such as an email or SMS OTP.

- Technology continues to rely on passwords - Removing passwords depends more on architecture and technology choices and is a trade-off between mission delivery and budget. Some platforms require passwords even if they are masked and stored in background processes. The only option at some point is to modernize from legacy systems (e.g., Active Directory and Active Directory Federation Services) to modern options that do not require passwords or use passwords in the background.

- Confusing lexicon - Derived PIV, alternative authenticator, FIDO Token, FIDO Key, WebAuthn Login, different authenticator, Derived FIDO credential, etc. Context is important when using terminology. For this playbook, a Derived PIV is defined by NIST Special Publication 800-157 as a PKI credential issued based on proof of possession and control of a PIV Card. Any other type of authenticator is an alternative authenticator. NIST is updating 800-157 and may expand Derived PIV requirements to include non-PKI options.

Lessons Learned

- No authenticator type is a silver bullet - Agencies need a holistic authentication strategy to stop handling access exception policies. There is not a single authenticator type that works across all authentication patterns and is phishing-resistant. Agencies must be comfortable with platform-native phishing-resistant authenticators like FIDO2 to replace the most common exception policy alternatives like passwords and OTP that are not phishing-resistant.

- User training and guidance - Plan and produce user guidance and adoption campaigns across agency ICAM programs. One of the biggest challenges in deploying new technology is ensuring you don’t lose your users on the journey. Hold office hours and Ask Me Anything sessions, or have on-demand videos to educate users and help them transition to new tools. See the user experience section of the Windows Hello for Business Playbook as an example. FIDO brown bag presentations are another good resource for engaging and learning about phishing-resistant authenticator products and services. Contact icam@gsa.gov to get added to the group.

- Platform authenticator cost advantage - FIDO2 platform authenticators provide a more straightforward and cost-efficient approach to meeting broader organization adoption of phishing-resistant authentication for all users. Biometric options such as face and finger recognition are supported in FIDO2 without needing 3rd party middleware but depend on device support and using modern access management tools (e.g., not natively supported in legacy tools such as Active Directory, Active Directory Federation Services, mainframes, and Siteminder).

- Challenge organizational assumptions - Large organizations with digital identity functions spread across multiple teams experience a high barrier to change. Many commonly believe they must only use a PIV credential or PKI with no alternatives. Challenge those assumptions as you promote more resilient authentication solutions or request a phishing-resistant authentication workshop from the General Services Administration at icam@gsa.gov.

The table below outlines the completion status of the FIDO CoA Cohort 1 and 2 pilots. See the FIDO pilot use cases section for the use case description.

Table 01. FIDO CoA Cohort 1 pilot with results

| Agency 1 | Agency 2 | Agency 3 | Agency 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Case | Back-up authenticator / outside of CONUS employees | Alternative Authenticator | Technology limitation / cloud environment | Alternative authenticator / mobile device |

| # of Pilot Users | 30 | 25 | 500 (Full Production) | 8 |

| Architecture | Platform: Okta Authenticator: RSA DS-100 & WebAuthn |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business |

Platform: ForgeRock Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

| Result | Piloted. | Moved to production. | Moved to production. | Piloted. |

| Agency 5 | Agency 6 | Agency 7 | Agency 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Case | Ineligible PIV user / business partner | Technology limitation / cloud environment | Alternative authenticator | Alternative authenticator |

| # of Pilot Users | 5 | 27k (Full Production) | Pilot - 200 / Production - 130k | 4% of Exemption Policy Users |

| Architecture | Platform: Vanguard Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business & Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business & Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Azure Active Direcotry Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business |

| Result | Piloted. | Moved to production. | Moved to production. | Piloted. |

Table 02. FIDO CoA Cohort 2 pilot with results

| Agency 1 | Agency 2 | Agency 3 | Agency 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Case | Alternative authenticator | Ineligible PIV user / mobile device | Ineligible PIV user / mobile device | Alternative authenticator |

| # of Pilot Users | 5k | 300 | 100 | 10-50 |

| Architecture | Platform: RSA SecureID FedRAMP Authenticator: DS100 |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business & Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Okta Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Agency IdP Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business & Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

| Result | Moved to production. | Piloted. | Moved to production. | Piloted. |

| Agency 5 | Agency 6 | Agency 7 | Agency 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Case | Alternative authenticator | Alternative authenticator | Alternative authenticator | Alternative authenticator |

| # of Pilot Users | 300 | 10-15 | 25 | 70 |

| Architecture | Platform: Azure Active Directory, Okta Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Okta Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

Platform: Azure Active Directory Authenticator: Windows Hello for Business |

Platform: Azure Active Direcotry Authenticator: Yubico FIPS Yubikey |

| Result | Moved to production. | Piloted. | Piloted. | Moved to production |

Phishing Resistance 101

While network attacks have become more complex, phishing remains one of the main tactics used to compromise credentials and infiltrate networks to move laterally and compromise data. In recent years, attackers have moved beyond phishing passwords to phishing OTP codes and push notifications that have been used to add a second factor to protect accounts. As CISA has noted, “Cyber threat actors have used multiple methods to gain access to MFA credentials,” using tactics such as:

- Phishing is a form of social engineering in which cyber threat actors use email or malicious websites to solicit information. For example, in a widely used phishing technique, a threat actor sends an email to a target that convinces the user to visit a threat actor-controlled website that mimics a company’s legitimate login portal. The user submits their password and the 6-digit code from their mobile phone’s authenticator app.

- Push bombing, also known as push fatigue, is where cyber threat actors bombard users with push notifications until they press the “Accept” button, granting threat actors access to the network.

- The exploitation of SS7 protocol vulnerabilities is where cyber threat actors exploit SS7 protocol vulnerabilities in communications infrastructure to obtain MFA codes sent via text message or voice to a phone.

- SIM Swap is a form of social engineering in which cyber threat actors convince cellular carriers to transfer control of the user’s phone number to a threat actor-controlled SIM card, which allows the threat actor to gain control over the user’s phone.

Even though a PIV credential is the primary authentication method for federal users and is phishing-resistant, many agencies rely on passwords, OTP, or push-based MFA when a user does not have a PIV credential. Agencies must focus on replacing these susceptible authenticators with phishing-resistant options. It is not a one-and-done swap, though. FIDO2 CoA members have noted these challenges that apply equally to all user types.

- Overall PIV challenges – A PIV credential is a single card that can be damaged, lost, or stolen. A user can’t be issued two PIV credentials as a backup if their primary is lost. Card readers are optimized for desktops or laptops, but more and more of the federal workforce uses mobile devices. Some agencies leverage a Derived PIV solution for mobile devices, but it is based on possessing a PIV credential. The PIV credential is only for federal workforce employees and contractors.

- Binding - Some agency risk decisions require a strong binding on the credential, which can’t be achieved through non-PKI methods. There is no government-wide unique identifier for PIV credentials. Most are unique within an agency or specific to the PIV card (e.g., the identifier changes when someone gets a new card). This creates a challenge in supporting PIV credentials from other agencies.

- Remote activation - Most members recognized a challenge with activating remote worker accounts using a phishing-resistant method. Most leveraged a step-up authentication process, such as physically mailing a code separate from the device and activating it over the phone with a help desk administrator.

- Authenticator software compromise or availability - FIDO is an industry-developed standard implemented through vendor software that could be susceptible to different software vulnerabilities. The same holds for PKI software. For example, over the summer of 2023, Microsoft patched a vulnerability in their PKI validation software, which broke PIV authentication. Agencies should identify and implement at least two phishing-resistant options if a PIV credential is unavailable.

Figure 1. Passwordless MFA

What is Phishing?

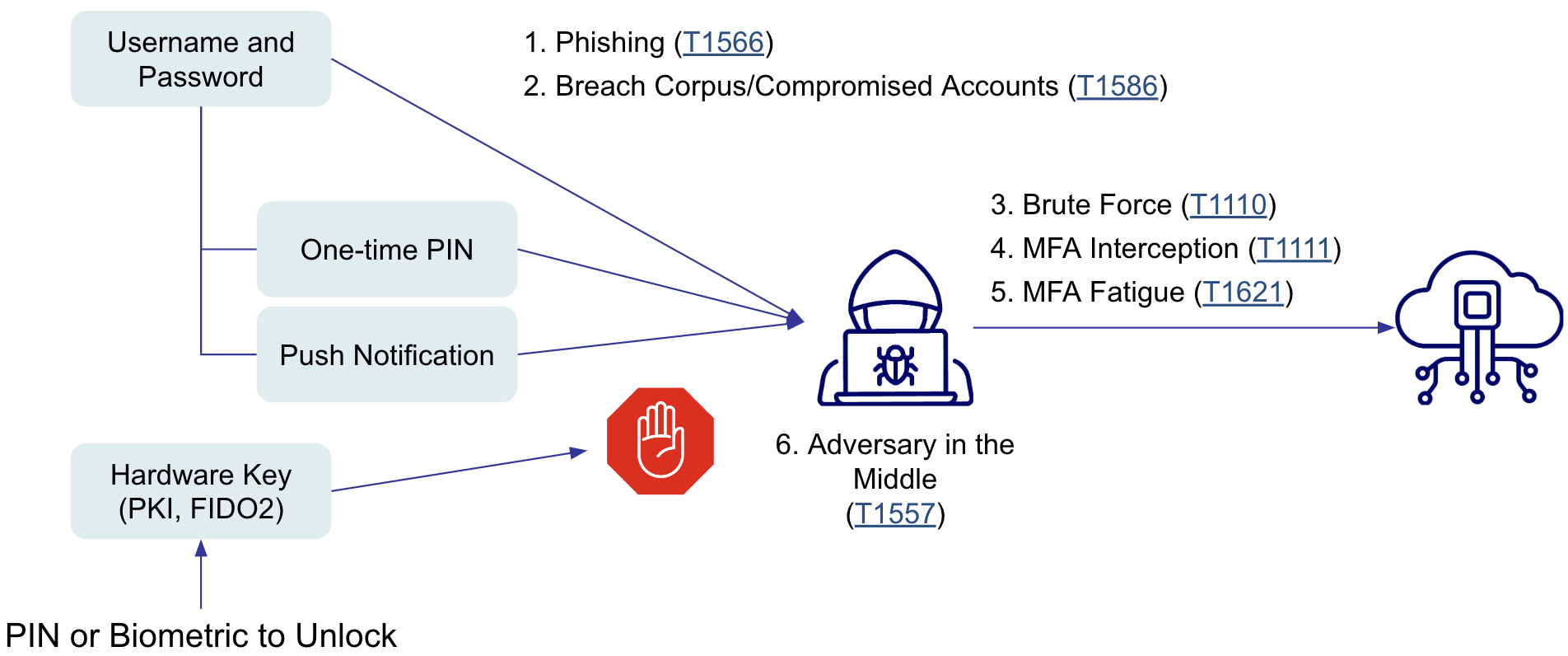

Phishing is a technique for attempting to acquire sensitive data or authentication outputs, such as passwords or OTPs, through fraudulent solicitation in email or on a website. In a phishing attack, the perpetrator masquerades as a legitimate business or reputable person. It’s not the only way an attacker acquires authentication outputs. Six MITRE ATT&CK Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures are commonly used for credential-based attacks.

Figure 2. MITRE ATT&CK TTPs for Phishing and Credential-based attacks.

Reconnaissance Phase TTP

- Phishing (T1566) - Phishing most likely are authentic-looking emails with a sense of purpose or urgency to click on a link or share information. Links can lead to fraudulent websites that either harvest credentials or deliver malware.

Initial Access TTP

- Adversary-in-The-Middle (AiTM) (T1557) – Adversaries position a network device to intercept communications which can include network sniffing or credential compromise.

- Breach Corpus (T1586) – It is very common for a user to leverage the same password across multiple sites, especially when a password manager either isn’t used or supported. A breach corpus is a data set of compromised usernames and passwords that can further be used in a credential access tactic.

Credential Access TTP

- Brute Force (T1110) - Guessing style attack using a breach corpus of compromised passwords or a new data set.

- MFA Interception (T1111) – Adversaries may target MFA mechanisms (i.e. mobile applications, token generators, etc.) to gain access to credentials that can be used to access systems, services, and network resources. This is often associated with SIM stealing for phone-based OTP, interception of OTP as an authentication factor, or other efforts to trick users into typing their MFA code into a phishing site.

- MFA Fatigue (T1621) – Adversaries may abuse the generation of push notifications to repeat login attempts continuously. This bombards the user with login requests until they potentially give in.

Does using phishing-resistant authentication really resist phishing?

Phishing-resistant authentication prevents phishing attacks that target the authentication process – in other words, stealing credentials. Some types of phishing campaigns attempt to convince the victim to open a malicious file or malware attached to an email, which is not an attack on authentication and thus not prevented by phishing-resistant authentication.

What is Phishing-Resistance?

Previous sections identified how credentials are susceptible to phishing and other attack types; this section identifies which types of MFA are phishing-resistant. Not all types of MFA are created equal, with some stronger than others. Phishing-resistant authentication is designed to prevent the disclosure of authentication secrets and outputs to a website or application masquerading as a legitimate system. The leading forms of phishing-resistant authentication include PKI (PIV-based, PIV-I, or Only Locally Trusted) and FIDO authenticators. Still, others may exist which implement some type of device or name binding between the authenticator, device, and application. Depending on the configuration, these authenticator types can be Authenticator Assurance Level (AAL) 2 or AAL3. Agencies should ask a vendor for documentation on their phishing-resistant claims or contact icam@gsa.gov for a collaborative review.

Table 03. Common MFA Options

| Phishable | Phishing Resistant | |

|---|---|---|

| AAL1 | AAL2 | AAL2 or AAL3 |

| Single Factor | Multi Factor | |

| Username / Password | 1. OTP (Email, SMS, Mobile App) 2. Push Notification |

1. PKI including PIV-based, PIV-I, and Only Locally Trusted credentials 2. FIDO2 |

These are phishing-resistant options because both leverage public key cryptography, which creates a public and private key pair.

- The private key is stored in a device TPM or secure enclave, making it extremely hard to compromise. In the case of PIV credentials or FIDO2 Roaming Authenticators, the private key is never shared or exported.

- The public key is shared with people or things like websites.

NIST Special Publication on Digital Identity Guidelines includes a list of requirements to meet their definition of phishing resistance, otherwise known as verifier impersonation resistance. Any authenticator that involves the manual entry of an authenticator output, such as an OTP, password, or other knowledge factor, is not considered phishing-resistant. Due to this design, an authenticator leveraging public key cryptography is more resilient to phishing and credential attacks. Using a PIN to unlock a device-stored key is not the same as using a PIN as an authentication output.

What is the difference between an authenticator and a credential?

A credential is an authenticator but also validates the person to the authenticator. A passport, driver's license, or PIV are examples of a credential, but they may also be a diploma or certificate. An authenticator doesn’t have the validation part. For example, a password without a username is an example of an authenticator. You don’t know who it belongs to, but someone can use it to authenticate something.

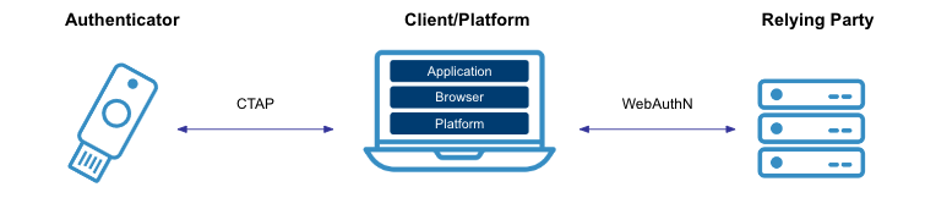

What is FIDO?

This section provides an overview of the FIDO Alliance and what they provide. The FIDO Alliance is a non-profit industry association of technology vendors publishing MFA specifications and testing and certifying vendor products against those specifications. For a technical summary of FIDO2, see the CISA Secure Cloud Business Applications (SCuBA) Hybrid Identity Solutions Architecture. Note that FIDO2 is sometimes described as WebAuthn authenticators. WebAuthn is a World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standard within the FIDO2 specification. FIDO first developed specifications in 2014, which included Universal Authentication Framework (UAF) and Universal 2nd Factor (U2F). This playbook only focuses on the FIDO2 specification.

FIDO2 is both a FIDO specification and a WC3 standard.

- FIDO Client-to-Authenticator Protocol - A simple protocol for communication between a roaming authenticator (such as a FIDO security key) and another client or platform over USB, Near Field Communication (NFC), or Bluetooth (BT). CTAP is a newer version of what was formerly called U2F.

- W3C WebAuthn - A W3C standard for javascript Application Programming Interfaces (API) to allow servers to authenticate users through FIDO2 authentication in browsers and devices. WebAuthn enables web services to support various FIDO2 authenticator form factors easily.

Figure 3. Example of a FIDO2 Authentication Transaction

A FIDO transaction for registration and authentication includes four main steps for each.

- Enroll a FIDO authenticator with a new online service.

- For services supporting a FIDO authenticator, the user is prompted to select an available FIDO option (usually available for a phone or tablet or a security key). The online service establishes the list of acceptable authenticator options.

- The user unlocks the FIDO authenticator, a separate process from unlocking the device, using a biometric, a PIN, or tapping the device. This unlocks the device to create a new key pair. Any biometric capture or use is on the local device and not shared according to the FIDO specification.

- The user’s device creates a new public / private key pair unique to the local device, the online service, and the user’s account identifier. A unique key pair is created per online service.

- The public key is sent to the online service to register the user and device to the user’s account in the online service.

- Login using a FIDO authenticator process.

- The user navigates to the online service and is prompted for the FIDO authenticator.

- The online service sends an encrypted challenge-response request. The user selects the FIDO option used to register with the service. They unlock the FIDO authenticator following the method used for enrollment.

- The device selects the appropriate user account identifier and key to sign a challenge-response request to the online service, which binds the user’s public key to the request.

- The device sends the signed challenge back to the online service, which verifies the signature with the user’s stored public key.

The FIDO2 authentication process conforms to the NIST 800-63 mechanism for verifier impersonation resistance. This includes establishing a protected channel, binding the channel identifier to the authenticator output, and the verifier validating the signature.

There are two categories of FIDO authenticators.

- Platform authenticator - Delivered via a secure, isolated execution environment (such as a TPM chip, Trusted Execution Environment (TEE), or Secure Enclave (SE) chip built into devices). One example includes Windows Hello for Business. Note Windows Hello for business differs from the consumer Windows Hello, which is not a FIDO platform authenticator.

- Roaming authenticator - Colloquially called a security key, a USB-A or USB-C-based physical device that can be used wirelessly across devices over NFC and BT. Some examples include Yubico’s Yubikey, Identiv’s UTrust, RSA’s DS-100, and Google Titan. If a PIV credential were also FIDO-certified, it would be categorized as a roaming authenticator.

You may hear FIDO authentication referred to as a “passkey.” This is a term that many companies are using to describe passwordless FIDO experiences; consumers are being urged to create a passkey instead of a password for improved security and user experience. Behind the scenes, a passkey is a discoverable FIDO-generated key pair, but the private key handling can vary. Passkeys may be:

- device-bound in a FIPS-validated cryptographic container, or

- synced across a user’s devices for increased usability. Passkeys, like PKI-based credentials, can be issued at an AAL2 or AAL3 corresponding to the keys’ lifecycle. Synced passkeys are well-suited for most consumer / public-facing use cases. However, enterprise applications can use attestation to distinguish device-bound passkeys from synced passkeys. Leveraging attestation in passkey implementations is similar to Object Identifier (OID) checking in PKI authentication. Vendor support for attestation in synced passkey implementations is still evolving, and passkey standards do not include assurance of passkey sync fabrics. Enabling syncable passkeys in enterprise tools is configurable and usually off by default. Verify with your tool vendor if they support it and how to turn them on or off. One potential enterprise advantage of synced passkeys is to improve the account recovery process. For more information on FIDO in the Enterprise, including choices surrounding synced passkeys, see these FIDO Alliance enterprise web resources and FIDO Alliance [Guidance for US Government Agency Deployment of FIDO Authentication]{:target=”_blank”}{:rel=”noopener noreferrer”}{:class=”usa-link usa-link–external”}.

Since FIDO2 leverages public key cryptography and can be hardware-based, it is categorized as a single-factor or multi-factor cryptographic device authenticator type. It achieves either AAL2 or AAL3, depending on the configuration and security control baseline.

Table 05. Advantages and disadvantages of platform versus roaming authenticator

| Platform Authenticator | Roaming Authenticator | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantage | 1. Single device; leverages the device's TPM as the authenticator 2. Potentially more cost-efficient than a Roaming Authenticator. 3. Most organizations may already have compliant devices. |

1. It can be used across both devices and operating systems. 2. Some also support PKI digital certificates. 3. Supports USB, NFC, and Bluetooth, if allowed by agency policy. |

| Disadvantage | 1. Usually limited to a single operating system environment (e.g., can not use an iPhone to authenticate to a Windows laptop). 2. Requires a device with a supported FIDO execution environment. 3. Potential for credential compromise if the device is also compromised. |

1. Added acquisition and tool cost. 2. Loss and damage are potentially greater/more common than a device. 3. Physical and logical credential lifecycle management activities include tracking, replacing, and renewing security keys. |

A Case Study on Authenticator Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity

Agencies should implement multiple phishing-resistant authentication options when a user doesn't have a PIV credential or the PIV validation infrastructure is compromised or unavailable. In May 2022, Microsoft released a patch that changed how PKI certificates (including PIV credential certificates) are mapped in Active Directory. These changes broke certificate-based authentication for many agencies that mapped PKI certificates using the User Principal Name (usually an email address). This patch also caught a lot of agencies off guard as they experienced rolling outages as Domain Controllers updated. For agencies that only relied on PIV credentials, this was a dire risk management decision to apply an agency–wide password exception or run vulnerable servers. CISA released guidance on applying the Microsoft patch outlining remediation steps which included applying the patch and turning on a compatibility mode. This compatibility mode is only temporary, and agencies must either manually or determine an automated way to update certificate mapping to a stronger method identified by Microsoft, such as by a subject key identifier. Some agencies took action to have a comparable alternative authenticator as either an ongoing secondary option or as a backup in case there is another potential compromise of PKI validation software or with PKI certificates directly. Microsoft may enable a Full Enforcement Mode from November 14, 2023, to February 11, 2025.

Run a FIDO2 Pilot

An agency’s journey toward leveraging multiple authentication options typically starts with a pilot. Follow these three steps from the FIDO2 CoA to plan and execute a successful FIDO2 pilot.

Step 1 - Recognize authentication patterns and use cases where your agency uses an exception authenticator.

Step 2 - Identify available solutions, which may include procuring FIDO2 security keys.

Step 3 - Deploy a pilot and make production considerations.

Step 1 - Recognize Authentication Patterns and Use Cases

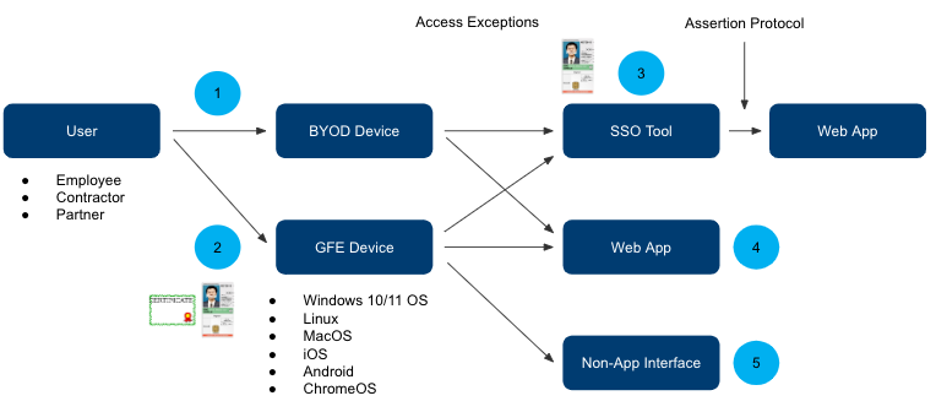

The first step for many agencies is identifying use cases, authentication patterns, and gaps. Figure 4 identifies the five most common authenticator patterns between a user and data and is grouped into two main categories.

Figure 4. Authentication patterns toward a holistic authenticator strategy

Device authentication is the first attempt to gain data access. Two device authentication patterns include managed and unmanaged devices.

- Unmanaged Devices include any device not under the organization’s control. Some agencies support Bring Your Own Device or contractor-furnished device access for a limited number of applications like email or collaboration tools. Deploying or enforcing certificate-based options, compliance profiles, or baseline images is difficult. This is a growing access method as more agencies support unmanaged device access to cloud applications.

- Managed Devices include any device under direct control or with a managed profile, such as Government Furnished Equipment and contractor-furnished equipment or personal devices with an organizational profile or container. GFE is the primary method most agencies use for data access. One challenge for most agencies is managing many operating system types, which may also limit how certificates are supported.

Application authentication is often the 2nd authentication attempt to gain data access. Three application authentication patterns include an enterprise Single Sign-On tool, direct access through a web application, or a non-application interface.

- Single Sign On (SSO) - Agencies are centralizing application access using an enterprise SSO tool. This is often where PIV enforcement occurs, with most SSO tools supporting certificate-based authentication.

- Web Application - Direct HTTPS authentication at a web page. The most common implementation is partner access use cases across agencies because most organizations have or are centralizing access to their internal applications with an enterprise SSO tool. Certificate-based options are often difficult to support, so most agencies deploy a password or OTP. Some agencies have outsourced authentication to a shared service such as Login.gov.

- Non-Application Interface - This is a catch-all for data access, not over HTTPS, such as command line, SSH, databases, or other non–HTTP protocols. Most agencies rely on either Privileged Access tools, Secure Shell (SSH) keys, or passwords with additional network-based access control such as a jump box.

Once we identify the authenticator gaps, we can identify the primary use cases of our holistic strategy. Four workforce identity use cases and one public identity use case identify where a phishing-resistant option can close those gaps. These are generic use cases that an organization can adopt or modify if they fit their mission needs.

Workforce Identity Use Case

- Alternative authenticator or “I don’t have a card reader” - This is the primary use case to replace exception authenticators like passwords or OTPs. This use case includes mobile device or application access where a certificate-based authentication option is unavailable or untenable. Agencies deploy an alternative authenticator like a platform authenticator as an always available option. Some agencies deploy Derived PIV. Another perspective of this use case is a bring-your-own authenticator for employees and contractors. Some agency systems can support it, and they’ve approved specific security keys, including contractor-furnished ones.

- Back–up authenticator or “I don’t have my PIV credential” - This use case user doesn’t have a PIV credential yet, meaning it hasn’t been delivered as a new issuance or a replacement. This use case replaces an exception policy authenticator with a phishing-resistant option until the user has their PIV credential. Some agencies deploy PIV Interoperable or agency-specific alternative tokens as well.

- Ineligible PIV user or “I can’t get a PIV credential” - This use case covers the user community outside the OPM credentialing standards. This community includes short-term employees, contractors, partners, and users who do not meet the continuous six-month access requirement. Some agencies deploy PIV Interoperable, agency–specific alternative tokens, or username/password and OTP.

- Technology limitations – Any certificate–based authenticator has challenges and limitations, as outlined in the 101 section. Cloud applications and mobile devices may not natively support certificate–based options, even with 3rd party tools. Partner applications are another example where maintaining a Federal PKI trust store is an untenable activity or creates user friction in using the applications. For example, there is no standard PIV unique identifier in the federal civilian executive branch government across agencies which creates a challenge for cross-government applications.

Public Identity Use Case

- Mission application for public users - The Federal Zero Trust Strategy recognizes that phishing-resistant authenticators are not just a workforce challenge but should also be an option for public users. Agencies should consider adding a phishing–resistant option to public-facing websites.

Can we support bring your own devices and authenticators?

It is an agency risk decision to support BYOD or Bring Your Own Authenticators (BYOA). A BYOA is a user's authenticator that they've personally purchased. Supporting BYOA is an everyday use case for applications that leverage an external access tool such as Max.gov or Login.gov rather than for an agency enterprise SSO tool. However, some agencies are exploring the benefits and risks of allowing employees to use personal authenticators. Consider data sensitivity when supporting BYOD and BYOA data access. One unique feature of FIDO2 is limiting the types of FIDO authenticators registered with an account. For example, an agency can limit to a specific vendor and batch of security keys (such as only FIPS-certified).

Step 2 - Identify Available Solutions

Most agencies are surprised that their agency enterprise SSO tool supports FIDO2, usually without any additional license or equipment costs. FIDO2 platform and device support require a crosswalk between operating systems and browsers, with some operating systems supporting some browsers and vice versa. FIDO2 platform authenticators are single operating system specific, so they will not work in a multi-operating system use case (e.g., Windows Hello for Business can not be used to authenticate to or on an Apple device). However, some cross-device workflows can enable a FIDO2 platform authenticator on a smartphone to be used to log in via a PC or laptop. Due to this, the user experience may also be different between operating systems and browsers.

Fortunately, the FIDO Alliance and their supported vendor community have several resources to identify platform and device support in addition to compatibility issues. They also have a growing base of vendor support, and more than 1,000 products have attained FIDO certification.

Five leading platforms and four browsers support FIDO2. Reminder: Not all platform authenticators work with all browsers. Always test for interoperability following your use cases.

- Platform (Operating Systems)

- Windows 10 or later

- Apple MacOS Big Sur (11) or later

- Apple iOS and PadOS 16.3 or later

- Android 7+

- Linux

- Browsers

- Google Chrome

- Apple Safari

- Windows Edge

- Mozilla Firefox

What's the advantage of a platform authenticator versus roaming?

Platform authenticators have some cost and user experience advantages over roaming authenticators. They are most likely supported on GFE and provide a more seamless experience than a roaming authenticator if a user only logs into a single device. Roaming authenticators are more widely supported in multi-operating system environments but come with the additional acquisition cost and lifecycle activities that come with a physical authenticator.

Public tools are recommended for verification and testing.

- https://webauthn.io/ is a Cisco / FIDO Alliance sponsored website to test WebAuthn. It also includes shared libraries and languages used to implement WebAuthn in web applications.

- https://webauthn.me/ is a Auth0 sponsored website to test and debug WebAuthn. It also includes a compatibility chart of which operating systems and browsers support platforms and roaming authenticators.

What about IA–2(6) control enhancement and platform authenticators?

NIST 800–53 control enhancement (IA-2(6)) requires that one of the factors is provided by a device separate from the system gaining access. This is not a baseline control but a control enhancement, meaning agencies are not required to implement it, and agencies handle the exception process. While this could mean a platform authenticator is not separate, another interpretation is the TPM (Windows), TEE (Android), or SE (Apple) on a device is separate from the device itself. Two OMB Memos (M-6-16 and M-7-17) also stated this control enhancement, but both memos were rescinded and shouldn't be referenced.

Identify Acquisition Strategy

There are two main patterns to acquiring security keys.

- GSA Advantage is a centralized acquisition portal that also includes FIDO2 security keys. Search for FIDO2 and verify if the vendor meets your requirements, such as FIPS certification. This is a good approach for purchase card or small quantities such as 100 or less.

- Some FIDO2 security key vendors provide enterprise contracts with additional benefits such as replacement and discounted pricing. These agreements often require large purchase orders of several hundred to thousands of security keys.

Because of the secure nature of a security key, acquire them from a trusted source and verify the packaging for tampering on receipt.

Step 3 - Deploy a Pilot

The next natural step is to plan and deploy a pilot. The FIDO2 CoA outlined a six-part pilot plan for a successful pilot. Agencies can add more sections, but these six should be included at least.

- Identifying objectives and use cases - This playbook is a great resource to help identify pilot objectives and use cases.

- Pilot size and executive support - Gain CIO and CISO sponsorship and identify a pilot user group commensurate with the production population. A pilot size should include users from the general population and not be limited to IT staff only. For most piloting agencies, this was 5%. Executive support can also include a video of them using the authenticator shared as part of an onboarding or training campaign.

- Timeline - Pilots range from a couple of months to a year, including all research and planning based on size and complexity. The actual pilot may only run for a couple of weeks.

- Pilot team and resources– Identify and engage with all stakeholders, including identifying a pilot lead and support team. For some agencies, this could include multiple teams spread across a network, directory, cloud, HSPD-12, security, and other offices. Also, identify your pilot components such as operating system, access tools, devices, browsers, and platform or roaming authenticator types.

- Risk and challenges – List your known and anticipated risks and challenges. These can include those listed in this playbook or agency-specific, like resource limitations or user adoption.

- Success metrics - There are a range of success metrics. Here are some examples.

- Remove passwords from our enterprise SSO tool as an authenticator option.

- Reduce the number of policy exceptions to less than 1%.

- 99% of user accounts have more than one phishing-resistant authenticator registered.

- Support two or more phishing-resistant authenticator options.

- Implement a self-service capability.

- Improve user experience survey results by 5%.

What is a good pilot size?

The FIDO2 CoA advises basing your pilot user size on a cross-section of production users (not inclusive of only IT users). A good size group is 50-100 users for platform authenticators and half that for roaming authenticators. The intent of a FIDO2 pilot should focus on validating enterprise use cases with an intent to deploy it in production as either an alternative or backup authenticator.

Lifecycle Management

All authenticators follow a similar lifecycle management process. For specific lifecycle questions regarding Derived PIV authenticators, see NIST Special Publication 800–157. A FIDO authenticator is registered to an account with most agencies following NIST Special Publication 800-53 controls covering account lifecycle management.

There are three lifecycle stages for a non-PKI authenticator, including FIDO. As part of lifecycle management, integrate help desk personnel on both pilot and implementation planning.

- Issuance

- FIDO2 roaming or platform authenticators only support hardware-based devices.

- Agencies should follow NIST 800-63 guidance that states a federally-issued authenticator be a FIPS 140 Level 1 or 2 device, depending on the required AAL.

- Agencies should ensure that the issuance process includes an MFA prompt at the same or higher AAL of the issued authenticator over a secured channel like mutually authenticated HTTPS.

- The authenticator is registered to an identity account in an agency ICAM system following the FIDO2 specification.

- PIN length is recommended as at least six digits.

- Register (or bind) the authenticator using a comparable Identity Assurance Level. See NIST 800-63-3 Section 6.1.1 on binding at enrollment. Agencies are encouraged to maintain at least two valid authenticators at existing authenticator levels to mitigate the risk of account recovery takeover.

- Maintenance

- FIDO2 authenticators do not have an expiration date or need to be reissued at set intervals unless they are compromised. Users should be reminded to use them regularly, monthly, or every 30 to 60 days.

- If the identity account is updated, it is possible that a new FIDO registration must take place.

- Platform authenticators may require biometric factors to be updated.

- Roaming authenticators that are security keys may require maintenance from normal usage or damage.

- Invalidation -

- A FIDO2 authenticator can not be revoked, but agencies can remove the association between the authentication and the user’s account, which occurs either at the device and/or at the application. This can occur if the authenticator is damaged, compromised, or deleted from the user’s device. This is similar to removing a certificate mapped to a PIV credential.

- If a roaming authenticator can not be recovered, an agency may consider suspending the user’s account.

Is FIDO2 a Derived PIV?

A Derived PIV is a PKI credential issued based on proof of possession and control of a PIV Card with additional controls as outlined in Special Publication 800-157. A Derived PIV is limited to a digital certificate in the NIST Special Publication 800-157 version. Still, the next draft version includes non-PKI Authenticator Level 2 and 3 options and associates other authenticators to the PIV identity record rather than just the PIV credential.

Best Practices with Biometrics in Authentication

Using a biometric platform authenticator can improve the user’s experience and be cost-effective because it leverages native device features. In the future, roaming authenticators may also support a biometric capability. Today’s most common platform authenticators include Apple’s Face ID, Touch ID, and Microsoft’s Windows Hello for Business. Android also supports a biometric platform authenticator but does not have a branded name. NIST Special Publication 800-63b outlines best practices when using biometrics as an authentication factor.

- As part of a multi-factor authentication, always use a biometric with a physical device (something you have) and never with only a knowledge factor (something you know).

- The biometric capture device uses a protected channel and is authenticated with the verifier before capturing a biometric.

- Operate with a False Match Rate (FMR) or False Accept Rate (FAR) of at least 1 in 1000 (<0.001%).

- Biometric systems should implement Presentation Attack Detection (e.g., liveness detection).

- Limit the number of failed attempts to five.

- Local biometric comparison is preferred over a central verifier.

Summary

A PIV credential remains the primary authenticator for federal users, but there are modern phishing-resistant options to create a more holistic authenticator strategy. These options include FIDO2 and WebAuthn, but more may be identified in the future. Many agency personnel are surprised that their agency supports these modern options. Agencies can use this playbook to pilot modern authentication options or deploy the technology into production to reduce or altogether remove passwords.

Appendix A - References

Policies

- OMB Memo 22-09 - Moving the U.S. Government Toward Zero Trust Cybersecurity Principles

- OPM Credentialing Standards Procedures for Issuing Personal Identity Verification Cards under HSPD-12 and New Requirement for Suspension or Revocation of Eligibility for Personal Identity Verification Credentials

Standards

Specification

- Web Authentication: An API for Accessing Public Key Credentials (April 8, 2021)

- FIDO Alliance including FIDO2 CTAP, U2F, and UAF

Guidance

- CISA Fact Sheet - Implementing Phishing-Resistant MFA

- CISA Secure Cloud Business Applications (SCuBA) Hybrid Identity Solutions Architecture - Technical Summary of FIDO2

- FICAM - Enterprise Single Sign-On Playbook

- FICAM - PIV-Interoperable 101

- FICAM - Configure Windows Hello for Business in Azure AD

- NIST Digital Identity Guidelines Frequently Asked Questions

- NIST Conformance Criteria for NIST SP 800-63B Authentication and Lifecycle Management

- NSA - Selecting Secure Multi-factor Authentication Solutions

Appendix B - External Resources

- PassKeys.io - This is a public tool to understand FIDO passkeys and test various devices.

- WebAuthn.io - This is a FIDO Alliance and Cisco sponsored tool to understand Web Authentication and test various devices.

- WebAuthn.me - This is a public tool to understand and debug Web Authentication and test various devices.

- CanIUse.Com - This is a public tool to identify which operating systems and browsers are compatible with WebAuthn and FIDO passkeys.